Adventures On The Plex Server #1

What's it all about? Plus Buck, Beatty, and a Bud-less Lou Costello

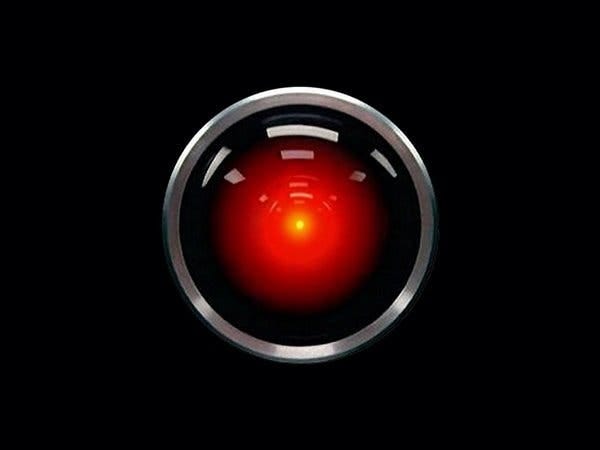

My mid-life crisis sits on a shelf underneath the TV in the family room, and its name is HAL-9000.

It started simply enough. It was early days on ‘80s All Over, and I was struggling to find a way to gather all of my research materials in one place. I was putting together the stacks of films to watch for the show, pulling in stuff on VHS, DVD, Blu-ray, and laserdisc, while putting out feelers to other film collectors for stuff that wasn’t readily available.

I finally stumbled upon a solution. I went out and bought a stand-alone hard-drive that I loaded with digital versions of all of my ‘80s stuff, and then I set up a Plex server. Plex is an app, a piece of software that you can download for free. You use it to index and access your digital media, whether it’s video, audio, or even photos. And, most importantly, you can share that server, so something that lives on your hard drive in one place can be screened on any of your devices, and on someone else’s devices as well. I set it up so that Scott Weinberg and Bobby Roberts, my collaborators on the show, could watch all of the movies that I could watch, and I was constantly working to get the films we needed ready and uploaded so we could record the show.

That show’s not in production anymore, of course, but the Plex server is still up and running, and it’s bigger than ever. I have spent almost three years now turning all of my physical media into digital media. Well, not all of it. There are still snowdrifts of discs here that I am trying to burn, and I’ll get through them all eventually or die trying.

There have been setbacks. I’ve gone through four different devices so far before ending up with a TerraMaster NAS server which works really well. Each of those devices died violently, and each time, I’ve had to start from zero. It’s a process. At this point, I have to treat it like it’s my hobby because it requires that kind of attention. The machine is always on, 24 hours a day, and it does crash. It’s as simple as pushing a button to get it back online, but it’s never predictable when it will or won’t go belly up.

I use my Plex server all the time, every day. I watch a lot of movies on Blu-ray, yes, but there’s something different about the ease of having over 8000 titles in one place, including several hundred TV shows, full runs of them. For one thing, I can treat it like a movie jukebox. I can go to a page with every single title on it, and I can hit “shuffle,” and I can let the machine do that, one film after another. I can also make playlists and either play those in order or use them as the loaded gun for a round of roulette. It gives you tons of control over how you watch your media, and I love it.

I have also been tortured by it when it didn’t work, and I have invested so much time and energy into it that it would pulverize me if Plex ever just plain vanished. It could happen, though. I’m well aware that an app like this could simply stop being updated, and that it could eventually stop working. The digital library I’m building is backed up in three places, so that’s not going anywhere, but the way I’m accessing it could, very easily.

I’m going to use this column as my version of a home video column. I will not just be talking about digital titles, but those will occupy most of my attention. Mainly, I want to talk about the way we watch/use movies. Because I’ll be the first to admit… I don’t give every film the same kind of attention when it’s on. Movies are such a part of the fabric of things for me that I do have different uses for them besides just sitting and giving them my undivided attention. Having your whole library available at the push of a button changes the way you digest things. I watch more films, more often, and a greater variety of them. And as I do, I find that it’s helping me get an overall picture of the way my attitudes on film have changed and developed over time. There’s nothing like that folding of time and space that happens when you watch a film for the first time in 40 years and you realize you have entire sequences from it still stored on your mental hard drive somehow.

For example, when someone passes away, it can be really wonderful to just pull up their career and dip into it, looking at favorite moments and scenes. That happened when Buck Henry passed recently, and there were two films I watched that stood out in particular.

Heaven Can Wait

Seven minutes and fifty-eight seconds.

That’s how long it takes Warren Beatty to die in Heaven Can Wait, the 1978 comedy that was co-directed by Beatty and Buck Henry. It’s remarkably efficient, but knowing Beatty’s process, I’m going to guess that wasn’t always the case.

The way I first fell in love with movies, I would get these sort of mini-obsessions where I needed to know everything about someone’s work, and I would go on marathons where I tried to watch all of it in a row, and it was illuminating in many cases because you could see the ups and downs of a career and you could really watch someone’s artistic life ebb and flow. One of those Mr. Toad manias that lasted a particularly long time was my Warren Beatty phase, and even today, I remain fascinated by his body of work and the ways he played with his onscreen identity.

I’m surprised it took me until my mid-teens to get to that Beatty phase, though, because for some reason, Heaven Can Wait was a staple in my house from the moment it was released theatrically. My parents took me to see it multiple times. One of the reasons I’ve always pushed to show my kids things that weren’t aimed at children is because I was raised in an era where parents often made theatrical choices based on their interests, and if you wanted to go along, maybe you’d get something out of the film as well. Films were less interested in what children might think of them. Our entire pop culture feels like it’s had the rough edges sanded off of it these days, and I like that I grew up in an era where something like Heaven Can Wait was thought of as family-appropriate.

A long-in-the-works remake of Here Comes Mr. Jordan, it’s a high-concept comedy about an athlete whose guardian angel pulls him out of harm’s way an instant before what he assumed would be a painful death. Turns out, it wasn’t the athlete’s time yet, but it’s too late. His body is gone. Heaven, realizing they screwed up, tries to find him a replacement body, and he ends up not only falling in love but also deeply invested in what this new body might be able to do in the world. It’s a fable about going from being selfish to selfless, and it is a very busy farce, and a lot of it probably shouldn’t work, but the script by Beatty and Elaine May is nimble and funny, and the supporting cast couldn’t be any better.

I’m haunted by the idea that Beatty originally wanted to make this movie with Muhammad Ali as the star. Can I live in the simulation where that actually happened? Because that sounds so fucking good. I know Beatty was a demanding collaborator, but there were people who worked with him repeatedly and watching him with Jack Warden or him with Julie Christie, you get a sense that these people are just throwing fastballs back and forth, all of them working at the very height of their ability. For me, much of what I love here involves Dyan Cannon and Charles Grodin as the unfaithful wife and murderous employee of the man whose body Beatty takes over, the two of them confused and horrified by the ways their various attempts to bump him off keep going wrong. There’s a Wile E. Coyote/Road Runner vibe to that storyline, and it gets funnier and funnier as it goes.

What’s amazing to me is how strong the theatrical experience can imprint on you. Watching Heaven Can Wait recently, for the first time in god knows how long, I found myself having strong sensory flashbacks to sitting in those packed theaters in 1978, waves of laughter breaking around me as the butlers keep tracking Beatty down in closets having heated conversations with himself or as Buck Henry, the frustrated guardian angel, keeps having to explain rules to an indifferent Beatty doing push-ups in the clouds. I remember the reactions of the crowd, and I’m sure that at least part of my affection for the film after all this time was just feeling that connection, wanting to know why all of those jokes were funny, and loving the overall experience.

Taking Off

Here’s a film that has only, to the best of my knowledge, been released in the UK on Bluray and DVD. One of the other benefits of turning everything digital is that I no longer have to juggle the four different players I was using to watch region-free titles, Blu-rays, DVDs, and even laserdiscs. I’m glad I picked up the things I picked up on each of those formats (I had some HD-DVD as well), but what a pain in the ass it is to have to keep all of that stuff hooked up.

I knew I had Taking Off, which I’d picked up because of Milos Forman, but I really didn’t know what it was. That’s part of being a movie hoarder. You have things you don’t even know you have sometimes. If I had any idea how great Taking Off was, I would have watched it before Buck Henry passed away. Instead, I got this amazing treat, this beautiful, strange comedy about two solidly middle-class citizens, Lynn Carlin and Buck Henry, who are shocked when their teenage daughter disappears. They’re in the middle of a dinner party with another couple, and as the crisis unfolds, they drag the other couple into it. Buck Henry and his buddy go out into New York in search of her, while the women stay at home freaking out. It’s a wild social comedy about changing mores and about trying to understand your kids, and I can’t believe it’s not better known and more beloved.

There’s this audition footage for a Broadway show that is intercut with the whole film that only gradually starts to connect to what you’re watching, and it’s this whole other amazing thing full of glimpses at actresses and singers who weren’t quite famous yet. Carly Simon, Jessica Harper, and Kathy Bates (who is billed here as Bobo Bates) all show up, and both Bates and Simon sing full songs they wrote themselves. There’s a long sequence involving Paul Benedict and Audra Lindley that is amazing, and throughout, both Lynn Carlin and Buck Henry are just terrific. Inventive, funny, surreal, and sharply satirical, Taking Off is one of those quiet gems that should be included in any conversation about the most savage looks at who we were in the late ’60s and early ‘70s, and how the generation gap was swallowing people whole.

Outrageous Fortune

I hadn’t seen this since it played theatrically. During that stretch of the ‘80s, I was working at a movie theater, and I saw everything that played in Tampa. Everything. I could go to any of our theaters, and we had six or seven different complexes in different parts of town, and since I had my own car, I would happily drive and pay for whatever we didn’t play. I was relentless. That meant I saw a lot of things I had no particular interest in, just to see them, and at the time, I was a teenage boy. So, no… I was not the target audience for Outrageous Fortune. When I see the awful discourse online and I see men who get angry about movies that aren’t made for them, there is a very small part of me that understands, because there was a point in my own emotional and intellectual development when I felt that way. But that’s because I was a child, basically, just taking the first steps into play-acting at adulthood, and I felt like the world was about me. Like it was centered on me. And I felt that all things should be made for me and service me and interest me, and anything that did not was bad. I was, quite clearly, a moron. And I grew out of it.

One of the wonderful things about growing out of that kind of myopic world view is that you get to enjoy so many more things. Teenage Drew did not get the appeal of Bette Midler, because Bette Midler is not, and never has been, particularly interested in whatever the fuck a teenage boy might want. And good for Bette Midler. She is, of course, an amazing performer, and the pleasure of Outrageous Fortune, such as it is, comes from watching Midler bounce off of Shelly Long, who was in the middle of her big run at box-office stardom. Bette was one of Touchstone’s good luck charms in those days. It was a match-up that felt inevitable once those first trailers came out. They’re very different actors, with totally different comic styles, and they’re both so sharp and on their game here that they make the most out of fairly thin material. Just watching Bette Midler walk in some of these scenes is funny. They’re that good at what they do. Arthur Hiller spent much of his later career trying to duplicate the success of Silver Streak, and those films all sort of shamble along being moderately funny without any of them really being memorable or compelling. Outrageous Fortune is one of those Touchstone high-concept comedy films that all blurred together for a while in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, all of them with identical scores and the same color palette and the same kind of just-enough-money-to-get-it-done overall production quality, and if you’re a fan of it as a comfort food entry, I get it. Leslie Dixon’s script is, like most of her work, at its best in the lighter sillier moments, and in somehow making the most ridiculous premise make some sort of sense.

27 minutes into the film is the best scene in the movie, and honestly, it may be the reason the film got made. I can imagine it delighted everyone involved, and it plays like gangbusters. The film’s premise is that these two opposite women cross paths a few times, disliking each other intensely. They don’t realize they’re both dating the same guy, and when he’s blown up in what seems like a random terrorist attack, they meet at the morgue, where they both come to mourn. They fight and then end up accidentally pulling the sheet off of his body, and as they stand over him, in tears, they both look down at his crotch and play the same moment of realization. It’s not him. And honestly, they both kill it. It’s a perfect beat in a scene, and they’re both hilarious as they notice all the details that are wrong, details that you would only know if you’d really been intimate with someone. It’s clear throughout the film that it was toned down from a rougher version. It’s an R-rated movie, but Touchstone’s R-rated films were still fairly mild-mannered as R-rated films go. There are a number of moments here where it’s clear they looped a tamer version of something over the original, and Bette Midler offers someone a blow jCAR HORN SOUND EFFECT at once point. It’s the kind of tiny cosmetic surgical scar that speaks to fine-tuned corporate tinkering.

The 30-Foot Bride of Candy Rock

Wait, what? Why would I talk about this one?

This is what I love about loading up the Plex with everything I’ve ever been sent. I forget why this was sent to me, but at some point, it was, and I set it aside. It went into one of the books, and then eventually, it ended up in a stack of stuff that I converted, and it finally, one morning last week, popped up when I hit shuffle play. Sure. It’s just over an hour. Why not?

What I found fascinating about this forgettable goofy sci-fi comedy is the idea of Lou Costello as a leading man without Bud Abbott attached at the hip. Their relationship was so complicated, with Costello controlling much of it thanks to the way he built the business arrangement between them. By all accounts, Costello was broken by the accidental death of his infant son, and it changed who he was as a performer. If his son had lived, who knows what would have happened with Lou? He was such a charming comic presence, and so clearly the engine in the Abbott and Costello dynamic, that he could have easily made the jump to solo work. I wish directors had seen him that way and that Universal had been bolder about how they used him. Hell, Bud Abbott could have had a great career just playing fast-talking sharps for filmmakers as well, but I don’t see him as a lead. It was Costello who always seemed like the one that you’re compelled to watch. Part of it was the comic persona he created, this sort of sweet man-baby who somehow retains a childlike manner while also clearly enjoying adult things. Part of it was a killer sense of what classic vaudeville bits would or wouldn’t work in a more modern context. He was like a Robin Williams, a guy who had seen and heard everything and who could drop into those comedy rhythms at the drop of a hat. He just plain knew how to work a scene. He made it look effortless, but there was a ton of craft in how he did it.

He died not long after this film came out, and I doubt it would have changed his career if he’d lived. He looks tired in the film, and even when you see glimpses of that charm that made him such a box-office sensation for so many years, the film around him just isn’t very good. But I love the idea of casting him as a sort of Absent-Minded Professor type for a goofy sci-fi comedy, or even a series of them. That’s a perfect fit. And you can see how he could have worked in light romantic comedies as well. If he did lose his taste for comedy after his son’s death, who can blame him? Maybe Hollywood should have leaned the other way with him. While we’re asking for alternative Hollywood histories, can I see the timeline where Costello got Oscar-nominated for starring in Marty?

Looking Ahead

I’m not sure how often I’ll do this one, but I will admit my underlying motive here so we’re clear and so you don’t feel like I’m trying to pull one over on you. I want more people to take their physical media and do the same thing with it, and I want more people to use Plex. The more users it has, the less likely it’s going to go away any time soon.

And if there’s a better alternative out there, then I want to know about it. My ultimate point here is that I want to control how I ingest these films I own, and I don’t want to have to rely on Netflix or Hulu or Disney Plus to provide me everything since they’ve made it clear that they won’t. Hell, just yesterday, I watched The North Avenue Irregulars on my Plex server, a title that isn’t available on Disney Plus. There are other titles from their history that I have that I doubt will ever show up on the service, and it will always be weird to me the way they handle their vault titles. Until the studios decide to just charge us a subscription fee for full access to their archives each month (the endgame in the promise of streaming media), the best option I have is to make my own library.

As my thinking on how to approach this digital future evolves, so will this column. The point is that we’re all figuring this out together right now, because there is no real standard for any of this, and I’d love to encourage other people to take control of their own libraries in this way.

Keep in mind… I’m not getting rid of the physical media. I keep all the DVDs in these big books (300 titles to a book), and I keep those in a closet in the TV room. I have all the Blu-rays on shelves, still in their original cases, but that’s starting to get unwieldy.

I know many of you are building digital libraries through companies like iTunes, buying your films there, and I get it. I buy a shit-ton of books for my Kindle. Or, more accurately, I license them for the Kindle, since anything that is locked down by DRM is not really owned by the consumer. I accept that with the books I buy for Kindle, but I do so knowing that my ownership of them may be illusory. I don’t know why I’m willing to accept it with books but not movies. Maybe it’s because the stuff I really really want to keep, I buy physically because it’s ingrained in me. Books go out of print for so many legal reasons that I feel like the only way you can ensure permanence is to own a physical copy. If Amazon has to, they can pull the digital copy from your Kindle and they can refuse to replace it. That’s in the terms and conditions you agree to, and there’s no recourse if something you bought just vanishes one day for legal reasons. The movies you buy on iTunes are the same way. You “own” them as long as you stay in the Apple ecosphere. Same with Vudu. It’s deeply frustrating to me because it’s the real reason they’re moving away from physical ownership. With movies, I can’t accept the idea that something might disappear. I want all of it. Every title I own, I want to keep. When I make my own digital copy of a film I own on Blu-ray or DVD, I can do whatever I want with it on my Plex server. And when I find another player I like better someday, I’ll just move my whole library over. The films exist my 16TB server, and Plex is just the way I read them. I’ll keep backing up the library as it grows, and I’ll be able to migrate that library wherever I choose because I don’t have any crazy weird restrictive software telling me otherwise.

I’m curious about the way you guys are approaching all of this these days, and I look forward to turning this into a conversation once paid subscriptions kick in.

For now, I’m signing off so I can go watch Ulzana’s Raid, which just popped up in the shuffle play…

Image courtesy MGM/UA Home Video

My plex server sometimes feels like my life's work. My favorite thing to do is make little film festival playlists for my pals. Great stuff as always.

Just subscribed after years of following your work on AICN and elsewhere. Thrilled you're hanging out your own shingle. I love PLEX. Now I will fantasize about being able to share your plex. I've got...ummm... Wonderfalls? ....fan HD remaster of DS9? ....Pretty please?