IPocalypse Now

Some thoughts on MEGALOPOLIS, THE SUBSTANCE, and the power of narrative

Hi. Remember me?

The Big Secret Thing That Is Still Secret is taking a few more halting steps forward. For the moment, I’m not “working” on it, but the amount of work I’ve put in to get to this point is kind of mind-boggling. My producing partners remain the absolute best people I’ve ever worked with, and the version of the thing that exists right now makes me very proud and happy. I hope it’s going to go further, but one of the things I’m learning to appreciate in the modern media hellscape is to enjoy every step as a complete experience. If the one thing that comes out of all of this effort is that I got paid to write something I like and that I got to work with people I respect, that’s a huge win for me overall. And if it goes further? If you someday get to actually watch it on whatever screen it is you prefer? Well, then, that will be a totally separate experience, and a totally different personal victory.

I’m at one of those moments when anything could happen. We’re leaving solid ground and launching ourselves out into space with the faith that we can fly or at the very least that there is a safety net down there somewhere. Creatively, this is always the moment when I am at my most chaotic. I can’t help it. I hate playing Schröedinger’s Screenwriter, but I understand that this is the choice we make when we commit ourselves to doing this over and over. It’s a crazy time to be working in film and television. There has, in my experience starting in 1990, never been a crazier time to work in film and television. It’s not even close. It feels like the wheels are coming off of a car that just nudged the needle past 100mph, and someone just reminded us we forgot to install brakes. People who have been doing this much more successfully and for much longer than me have expressed their feelings about the chaotic nature of things to me in some very frank conversations, and it’s hard not to feel some anxiety. But that’s just what it is to work in this business now. People who used to feel incredibly secure are scrambling, and people who used to have to scramble are leaving the business completely.

So why?

Why did I decide to try again, despite my having retired from screenwriting?

I am a firm believer in the power of narrative.

If I wasn’t, the last few decades of my life would feel like a waste of time and energy. I think there is real value in creating narratives we share, above and beyond the commercial enterprise. When I was young, I often found myself defensive when people would talk about people who did terrible things “because of” some media they watched or read or listened to, saying that movies couldn’t make anyone do anything. I still think it is superficial and wrong to blame media for the behavior of any individual, but my feelings about the power of media have changed completely. I think narrative is enormously influential in all kinds of ways, and more than ever, the world we live in is shaped by opposing narratives competing to define reality as we know it.

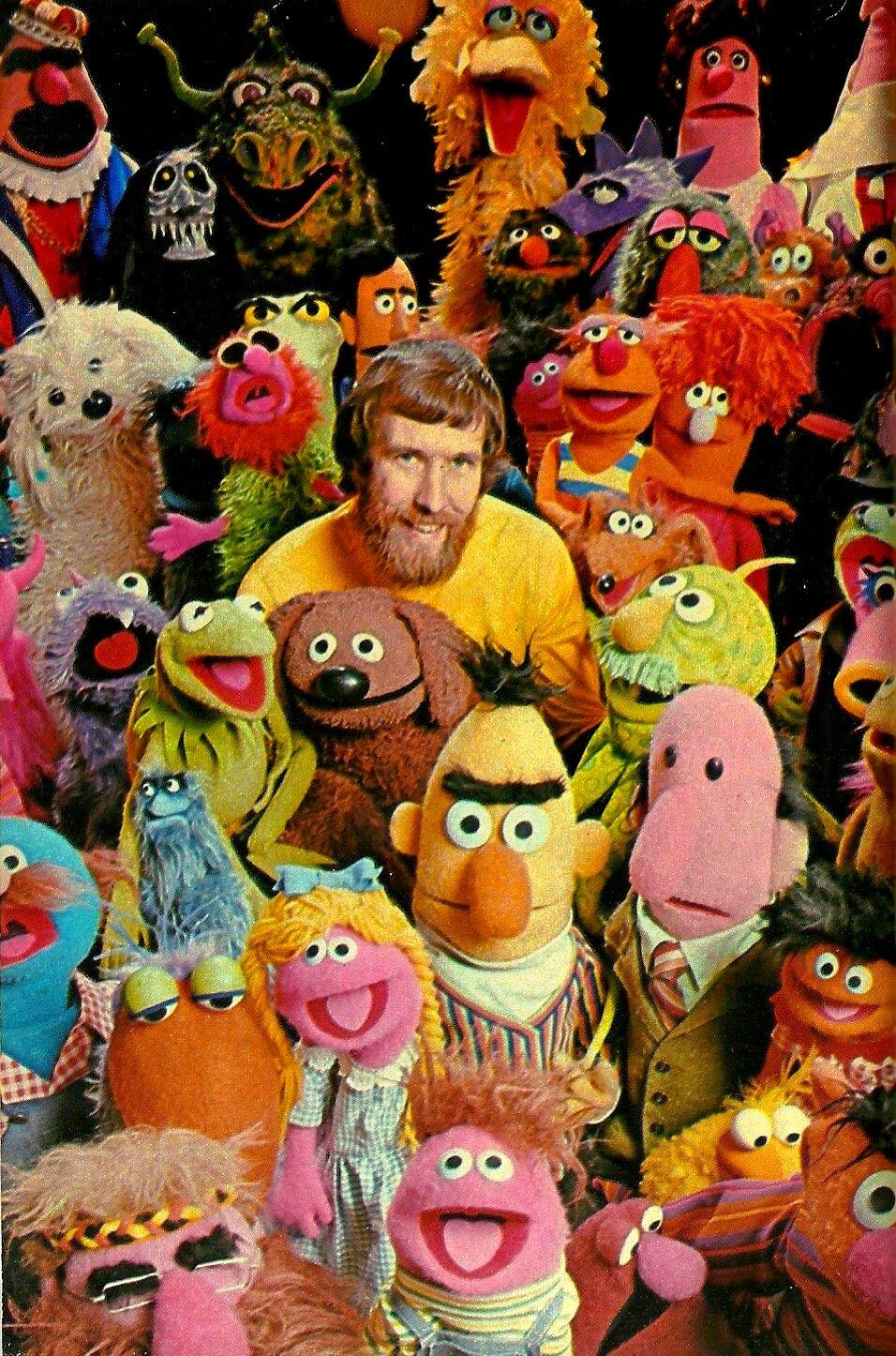

Screen Drafts recently released an episode for their Patreon supporters where their six “Legends,” people who have done twenty or more drafts for the show, picked the 25 best TV shows of all time. The results were chaotic and hilarious and filled with personal picks while leaving off some all-time greats… you know, like pretty much every episode of Screen Drafts ever. One of the shows that Graham Skipper picked was Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, which led to a discussion about how influential the show was, and how Sesame Street occupies much the same cultural space. When I think about the way media can or can’t influence people, the ultimate argument I can offer up from my own life would be the one-two punch of those two PBS programs. I started reading actual books at the age of three, and that is entirely because of my steady diet of Sesame Street, Electric Company, and Mr. Rogers. My parents thought the idea of the Children’s Television Workshop and PBS was a good one, and they saw an immediate result in my case. I hadn’t even started school and one day I picked up the newspaper and read them the front page.

If that was the only impact from those shows, that would have been enough, but both Jim Henson and Fred Rogers had much deeper impacts on me. I don’t think I’ve always lived up to the ideals their work instilled in me, but I constantly return to things I saw and learned in those early formative years. Whenever I watch anything, I am looking for things that make me feel. I do not approach films or television shows as background noise. I am looking to engage fully, and I want to be challenged. I don’t want to simply reinforce my own point of view or my own experience in the world, either. A pivotal moment for me as a young film fan came when I saw Pather Panchali and spent a few weeks dreaming of this totally alien cultural experience. I realized films offer us a chance to see the world through anyone’s eyes, and to understand any experience. It’s a language that is used to communicate, and I’ve spent my life digging into both the meaning of this media and the process by which it’s made. I’ve done my best to fully learn that language and to understand all the applications of it. I’ve spent time and energy on this because it matters, and yet here I am, 54 years old, and I am utterly baffled by the way a big chunk of the world watches things.

Beyond baffled, actually. And I’m not sure if it’s simply the Internet giving us more access to each other’s every thought or if it’s the rise of the Fox news bubble, but it feels like there are more people than ever operating in bad faith or who don’t seem to understand the media they’re watching. I’m not sure which it is, and even now, there’s a part of me that still wants to give people the benefit of the doubt. I would prefer to believe that someone is media illiterate instead of thinking they are intentionally terrible. Clearly, Fox News viewers are just as addicted to narrative as everyone else, but the narrative that they crave is a narrative about the world that reinforces everything they already think and fear. They are soaked in fear, and that fear has real-world ramifications in the way they vote, the way they talk, the way they treat their neighbors. Even more frightening is the way they lean into a narrative that denies the reality of the world outside their television screen, one in which babies are being murdered after being born, pizza parlors hide secret sex dungeons, and political elites are both coordinated and competent enough to orchestrate the most elaborate and successful conspiracies that are also somehow well-documented by random anonymous internet posters. Our modern media landscape has made room for the fringe in a way that means there is a percentage of the population that no longer believes anything that is real. If you want to believe lizard people operate out of a secret base on the continent that lies on the other side of the wall around the edge of our flat earth, serving interdimensional masters with nefarious agendas, there is just as much room for you in the mainstream now as there is for people who accept science as, you know, a fact.

We want to be part of a narrative, and that desire can be strongly compelling. I understand why people love cosplay. I would imagine it scratches some of the same itch that I satisfy by playing licensed videogames set in the worlds I love. Right now, I’m playing Star Wars: Outlaws, and the game I played before that was Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora. In both cases, the gameplay is fun, but familiar. If you’ve played any Ubisoft games (and I’ve played soooooo many Ubisoft games), then you know that they’re all just versions of one another. They reskin their basic gameplay ideas and evolve them slowly over time, but there are some basic Ubisoft mechanics you start to recognize if you play enough of what they produce. The only real difference is which world you’re in, and obviously, that’s enough to get me to pony up time after time. Playing a mission where I have to disguise myself as a Stormtrooper so I can walk one of my buddies through an entire Star Destroyer is about as close as I’ll ever get to living in the world of the films, and with games, something different than films happens. If you play a game for enough time, you get a sense of these playing spaces as actual places that you’ve been. You start to remember the geography of Tatooine or Akiva or Kijimi like you’ve explored them in person because, in a way, you have. But when I’m playing these games or when people participate in cosplay, we’re not actually confused about reality. I don’t think I’m really in Star Wars, and people at ComicCon don’t think they can actually fight crime with superpowers. That’s one of the reasons it’s so upsetting to watch people wholeheartedly believe a narrative that is designed to divide people in the real world, pushing them into radicalized silos of misinformation that they don’t just watch… they bathe in it. They soak it up around the clock. And I’m not just talking about Fox, a network that has been forced to admit in court that they are not a news organization. I lost a friend to the Alex Jones pipeline, and I watched him lose his grip on reality in slow-motion. The longer he spent watching this entire alternative media ecosphere, the less connected he was to anything that resembled my friend. With him, that started on 9/11. When that happened, something in him broke, and the world just stopped making sense. He needed to find a story that would make sense of things, even if that story is completely insane. He was willing to believe anything that gave him a framework that was less terrifying, no matter how absurd that framework.

Hollywood has always been good at narrative, and not just on screen. The Oscars are an annual event in which Hollywood tells the world a story about itself. “This is who we are right now. This is what is important to us. This is why we matter.” That story changes every year, and it is often a mirror of the ways the world changes outside Hollywood. When I see someone complain that the Oscars have gone “woke,” a word I despise at this point because of the way it’s been turned into a pejorative by the worst folks, it seems to me that they haven’t paid attention to the entire history of the award. The Oscars have always been a narrative. Sometimes it’s about someone who’s overdue. Sometimes it’s a celebration of a new talent. Sometimes it is about making a statement about the world. The best narrative is often what wins at the Oscars, and that’s the one thing Harvey Weinstein had an almost savant-level understanding of… the way the Oscars love to vote for a great narrative. For a long time, careers have been narratives that are crafted by the industry as a way of contextualizing the products that they sell. Studios invested time and energy in building their movie stars and their star directors, and when the old Golden Age studio system collapsed, the super-publicists arrived, ready to carry on the work of telling public stories that were designed to sell a person like a brand.

The last decade has seen a strange disconnect take hold of the industry, though, and it feels like Hollywood’s relationship with narrative is broken. Narrative is not what drives the choices at the major studios right now, and not just on screen, and that feels like such a reversal from what has always been a fundamental part of every conversation, every decision, every bottom line, that I think many of us have no idea what to do in response. When I was younger, I used my bully pulpit at Ain’t It Cool to shape narratives around people like Lorenzo di Bonaventura and Tom Rothman, narratives that cast them as the villains in a battle over art. And while I think many of the fights I picked were for good reason, I look back at those tactics and I am filled with regret. I knew what I was doing. I was good at it. I could mobilize armies of anonymous nerds to get angry at people over creative choices they were making, and I have no doubt it was awful to be on the receiving end of that energy. It would be easy to do the same thing these days with David Zaslav, and I genuinely don’t think he’s been good for our industry in any way. But I also think those narratives are reductive, and they make it impossible for any kind of real conversation to happen. Once you’ve cast someone as the bad guy in your story, you’d be surprised how often they’re willing to play that part. And why should they? After all, in their narrative, they’re the hero, and you’re just someone who has decided to attack them while they’re trying to do their job.

I think the reason so many grifters on the internet have seized on Kathleen Kennedy as the all-purpose boogeyman who has ruined Star Wars is because they are afraid to interrogate their reactions to Star Wars in any serious way. It’s an easy narrative for them to blame one person for all of their feelings, but it’s ridiculous and reductive. I’ve been consuming Star Wars in one form or another since I was 7 years old, and I am 54 this year. That’s a long time, and it is inevitable that not all of that storytelling will work for me. It would be shocking if it did. The way I approach that is to watch what I feel like watching, not watch anything I don’t think looks interesting, and to treat it all like entertainment, not gospel. I really like Leslye Headlund’s The Acolyte, and I’m sorry there won’t be a second season of it. There are other shows from this Disney era that I don’t like very much, and if they end up getting a second season, I won’t cry about it. It is disheartening to hear that studios, unable to distinguish good faith from bad, are so freaked out that they’re trying to get ahead of any and all criticism from the very beginning. There’s an article over at Variety that talks about the way studios are or aren’t reacting to the weaponization of fandom, and it seems to me like an already bad situation is just going to get worse:

Those who did talk with Variety all agreed that the best defense is to avoid provoking fandoms in the first place. In addition to standard focus group testing, studios will assemble a specialized cluster of superfans to assess possible marketing materials for a major franchise project. “They’re very vocal,” says the studio exec. “They will just tell us, ‘If you do that, fans are going to retaliate.’” These groups have even led studios to alter the projects: “If it’s early enough and the movie isn’t finished yet, we can make those kinds of changes.”

Risk aversion and art do not easily co-exist, and that is one of the reasons the studios have leaned into an all-IP all-the-time diet as much as they have. The more they can smooth out anything that might potentially upset or irritate anyone, the more they feel like they’re putting out product that will be safely consumed by everyone. Just typing that makes me feel dirty. I didn’t fall in love with movies and books and comics because I thought they were well-managed brands that managed to sidestep any possible offense to anyone anywhere. I don’t think of stories as “product to be consumed,” but Hollywood does right now, and when that is the only mindset making decisions about what gets made, it gets increasingly difficult to make anything actually worth watching or caring about. You can certainly start from an IP and create a narrative that is interesting or exciting, but reverse-engineering will always be a somewhat mechanical process.

It cannot be stated strongly enough that pretty much every IP that Hollywood considers important came originally from a very personal place. J.R.R. Tolkien wrote his Middle-Earth books and stories and appendices because he had to. Those things were rattling around inside him, growing and growing, and putting them down on paper was essential for him. Star Wars could not be more of a personal vision in its original form, something that George Lucas could just barely articulate enough to get it on film. Ghostbusters was born out of the pure lunatic obsessions of Dan Aykroyd, and even if it had never gotten made, he would still have self-generated all of that dense mythology because that is the world where Aykroyd lives. When fans argue about what is or isn’t canon or what does or doesn’t honor the original, all of those opinions carry the exact same weight, which is none. It does not matter what I think is or isn’t Star Wars because I don’t own it and I’m not the person making it. The only thing that ultimately matters is what my own personal reaction is watching something, just as the only thing that should ultimately matter to you is your own personal reaction. Anything else is noise, and navigating a way through that noise to get to the thing is becoming such an unpleasant task that I think the lasting legacy of these “superfans” is going to be pushing the things they love back out of the mainstream because most normal people don’t want to be involved in anything that carries this much ugly, shitty baggage. The primary narrative now is that there are so many racist, sexist, reactionary creeps who are working the fandom space that it has overwhelmed any normal conversation that might exist, and if me saying that upsets you, you may well be one of those shitty reactionary grifter creeps. I refuse to engage with that narrative anymore. I refuse to give those people the energy. Every time someone debates them, it offers up some credibility to their arguments. After all, if you’re bothering to debate them, you’re treating their arguments as worth the time to discuss, and honestly, they’re not. At some point, we are building these creeps up into villains, and that in turn activates their shitty followers. The thing they are most afraid of is the thing everyone is afraid of on some level: being left out of the narrative completely. When you turn your back on Freddy Kruger and refuse to accept him as something to fear, he loses his power, and the same is true of these people and this kind of hate-driven media. You don’t marginalize them by amplifying them. You do it by treating them like they don’t exist at all.

Social media has made that difficult. The internet age has made that difficult. I hate that some of my early work at AICN was all about creating a narrative to effect a change and that I was damnably effective at it. We showcased a game plan that has metastasized into the thing that seems to omnipresent today, this organized echo chamber of demands that everything feed one particular infantilized flavor of nostalgia in which the world is forever frozen in a mostly-white mostly-male shape and size, and I am filled with regret over it. We showed fans how they could loudly demand changes in things, and no matter how many times I felt like we tried to do it the “right” way, it is so clear now that there is no “right” way. Narratives do not get better the more people you have shaping them. Just because you want something from a narrative does not make it right. And storytelling is not interactive at its heart. We tell stories to impart experiences, ideas, and emotions to one another, and when I’m telling you a story, there’s no question mark implied at the end of it. I’m not asking you, “Did I tell this right?” I’m telling you “This is the way I tell this.” When you demand that a storyteller change their voice to please you, what you’re really saying, as loudly as you can, is “I am the only important person, and anything I do not like is bad.”

Part of the fun of something like Disneyland is the way they created dozens of smaller narratives within the larger experience. When you queue up for The Haunted Mansion, they start telling you the story before you ever set foot inside. There are hundreds of small design details that are conveying story to you as you walk through the line, and it’s like that with all of the Disney rides. Your entire time getting ready for the ride is part of the story, and that’s true of the way we experience movies and TV shows now as well. We start interacting with things the moment they’re announced. Our reactions develop with each new piece of information, each casting announcement, each poster and picture and teaser and trailer adding something to our impression, and sometimes it feels like by the time we actually see the thing, we’ve already made our final decision about what we think. Predigested pop culture is exactly what the studios want. They don’t want to leave everything up to you either liking or disliking a movie. Too risky. They want to transform audiences into brand warriors, who not only show up to everything and anything connected to their IP favorite, but who do the work of the PR team, attacking anyone who dares say anything bad about their beloved property. In doing so, they’ve empowered divided fandoms, and now you’ve got people whose entire relationship with projects is attacking them from the moment they’re announced and then attacking them incessantly for as long as they can keep getting people riled up. I’m sure there are plenty of people editing some new video about why The Acolyte ruined western civilization right now, and they’ll keep hammering the same point from different angles as long as people keep clicking on the videos. Those people are committed to that narrative, and that’s how you get review-bombing on things that people haven’t seen yet. It’s more important to tell the story about how Kathleen Kennedy has personally broken into George Lucas’s house to murder each and every character he created than it is to examine why you are upset by the creative choices made by dozens if not hundreds of people who have now been able to play with the incredible sandbox Lucas created. It’s impossible that you, the viewer, might not be the same person you were when you first saw something several decades ago or that you might have biases you haven’t examined. No, instead, the story has to be that someone intentionally set out to ruin something because they hate what you represent.

When storytelling becomes sports, people start to want to win or lose, and that’s not the right way to approach storytelling at all. I’ve watched one of my sons become a rabid NBA fan over the last five or six years, and a big part of what keeps him addicted to sports is the ongoing narrative. The redemption arcs. The heel turns. The heroes who rise or fall. He loves it all, and he lives and breathes it even between seasons. He thinks about each team as a separate story being told, and the season as the way all of these different stories collide, and while he has his favorite teams, I think he’s just enthralled by the giant shifting organic narrative. It seems like a healthy way to be a sports fan. I know other sports fans who are miserable because the story that they are focused on never goes the way they want it to, and it almost seems like a form of self-abuse. If you look at the vast amount of media available to all of us at all times right now, and what you focus on are the things that make you so angry that you have to rant and cry and organize attacks on people and studios, then I would suggest you are doing it wrong. You like feeling bad. You like being angry. You are making that choice, and then you are inflicting that choice on the rest of us. The only antidote is making a choice about how we choose to interact with people who choose to be driven by fury or fear or rage or hate. I am all about people who spend their time highlighting the things they love, who are so busy enjoying all of the good work that’s out there that they just don’t have time to whine and bitch and cry. And while Hollywood struggles to keep the lights on by increasingly leaning on properties that they are also actively homogenizing to the point of irrelevance, I choose to keep shining a light on the good work that’s still getting made. We are in the meltdown days. The Julie Andrews in Star! days. The “nobody knows anything” days. And there is only one north star.

Narrative.

Not IP. Not AI.

Narrative.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Formerly Dangerous to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.