The Hip Pocket #19: ERASERHEAD

David Lynch's first feature film remains a landmark of surrealist cinema

We all have movies we love.

Some of them are great movies. Some of them are terrible movies. Love does not care. Love is unreasonable. Love is blind. We love what we love, and the louder you love it, the better.

One of my favorite things is sharing a film I love with someone. Even if they don't love it the same way I do, that experience imparts something about you to that person. When you share something you love, you are sharing a part of yourself, and there is nothing more vulnerable or personal than that.

I don't think of these movies as the canon or the official library or anything that formal. These are all just movies I keep in my hip pocket, movies I've filed away as part of my own personal ongoing film festival as worthwhile and notable.

This is an ongoing list, one without an ending. This is The Hip Pocket.

Eraserhead

dir. David Lynch

scr. David Lynch

Commissioned by Shawn Hoelscher

There is no filmmaker whose work strikes me at a more primal level than David Lynch, and here’s how I know that. Almost every time I’ve seen a David Lynch film, my first reaction has been immediate, furious anger and outright loathing. I have hated many David Lynch movies upon first viewing, but in every single case, I have later embraced those films as essential works of art, part of the reason I love film as a whole. The gap between those two reactions is what makes him such an ongoing source of fascination for me, as well as a filmmaker whose work I continue to grapple with each and every time I watch it.

My first exposure to this one came before I knew who he was as a filmmaker. It was because of the cover of Midnight Movies, one of the first books to turn me on to some of the craziest fare the world of movies had to offer. In the days before home video, I would haunt my local libraries looking for books about movies. There was the great Richard J. Anobile, who published these oversized hardcover books where he would blow up movie frames to recreate an entire film in book form. Those eventually morphed into the Fotonovel, but his Film Classics Library series was enormously influential for me. Danny Peary’s Cult Movies books were another early road map for me, as was the work of Pauline Kael. Collections of her reviews fascinated me, and I loved reading about movies I not only hadn’t seen but had no way of seeing any time soon. I felt like I was reading travel guides to exotic places and dreaming of the time I might get to go and visit for myself.

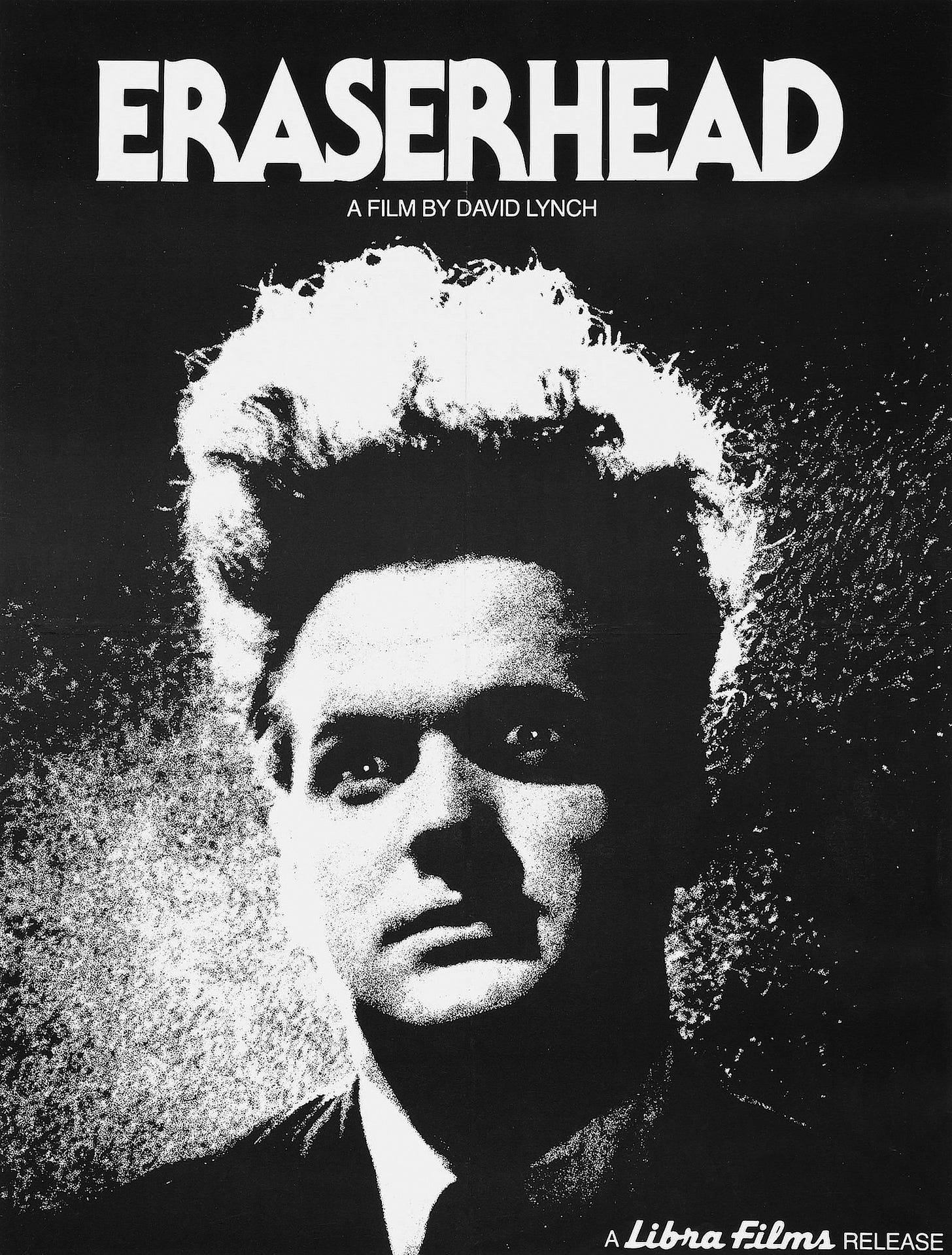

But when I saw that cover of Midnight Movies in 1983, it was a lightning bolt moment. Something about that image. Jack Nance in front of a strange black and white background, that hair of his almost seeming to be made of the light and the shadow. I devoured what J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote, knowing that I’d never track something as rare and exotic as Eraserhead down. There was no way I’d ever end up part of a world where you could just watch something like Eraserhead or El Topo. Those were like lightning in the wild, these dangerous things that happened far away that I might glimpse at a distance, but never close-up. Of course, today, I can look across my office from where I sit as I write this, and there’s a Blu-ray of El Topo (next to a Blu-ray of The Holy Mountain), both of them signed by Jodorowsky when we did a one-hour conversation together at SXSW a few years ago, and I realize that we have truly entered a blessed age where the obscure exists at our fingertips and in the most remarkable form we could have hoped as film fans.

It almost feels wrong to be able to summon up Eraserhead on demand. I can click three buttons on my computer any time I want and there it is, this thing that took David Lynch years and years to finish. It is only 89 minutes long and every single one of them feels like it took a war to produce. I can sum up what I feel it is about very simply: the anxiety of parenthood. But to say that and then to see the actual film, you get a sense of just how special film is in capturing the feeling of something. This is what makes it my favorite art form… it is the combination of writing and music and performance and sound and light and accidents and the brutal dictatorship of the editor. Film has to be produced collectively, but the end results can be so singular that we can attribute “authorship” to an individual. How David Lynch ever convinced any other human beings to help him make Eraserhead is a mystery, not because it’s a bad film, but because there is truly nothing else that compares to it. There’s no way any storyboards or screenplay or even pre-production art could fully convey what it was he was hoping to accomplish, but the end result is one of the most confident works of film art I’ve ever seen.

The opening moments of the film are perhaps the most audacious opening moments of any director’s first feature film. In a series of images that almost seem to evoke the title card from 2001: A Space Odyssey, we get Jack Nance giving birth through his mouth to a strange spermy thing while a man covered in lesions or boils watches a pit of primordial goo, pulling levers to ready it for the arrival of Jack Nance’s weird spermy thing. They collide, everything turns to bubbles, and then we find ourselves with Nance, playing Henry, as he makes his way across this landscape mainly marked with rubble and decay and industrial piping. That is, apparently, what fucking looks like in David Lynch’s world. Makes sense.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Formerly Dangerous to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.