Welcome to the actual show.

It took us a while to get to this point, but I feel like this is where we turn the last corner on a technical level and the show really clicks into place.

It also feels like the format of the show is starting to work at this point. It’s one thing to lay it out on paper, and it’s another thing entirely to actually run through it like a show. It’s also easier when you’re inviting on people you already know to some degree. While I’ve met Jason before and I certainly know his work, I wouldn’t say we’ve really gotten to know each other at all before this. As a result, this felt like the best test run yet for seeing how this would work with someone new to all of us.

JASON PARGIN is today’s guest, and he came ready to dig deep! No surprise if you’ve read his acclaimed novels like John Dies at the End, Zoey Punches the Future in the Dick, or This Book is Full of Spiders, or if you know his work from Cracked.com. He has a massive TikTok following these days and his latest book, I’m Starting To Worry About This Black Box of Doom, feels like an essential text for our turbulent times.

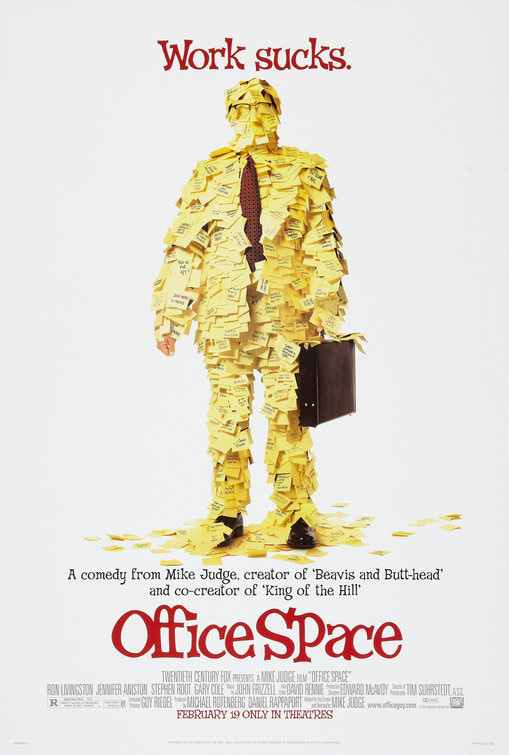

His three Hip Pocket selections were American Beauty, Fight Club, and Office Space, and I picked the Alan J. Pakula film Orphans as our response.

Finally, Drew inducted The Virgin Suicides into the Hip Pocket Hall of Fame.

If you’d like to support The Hip Pocket at Patreon, you can find us at https://www.patreon.com/c/DrewMcWeeny.

If you’d like to find us on BlueSky, you can find us at https://bsky.app/profile/itsthehippocket.bsky.social.

The Hip Pocket is hosted by Drew McWeeny and Aundria Parker.

Craig Ceravolo is the show’s bandleader and producer.

It is a Formerly Dangerous Production.

[the Hip Pocket theme plays]

DREW: Welcome, everyone. I'm Drew McWeeny, and this is The Hip Pocket.

What is a hip pocket movie? I think they're the films that we hold close to us, movies that we love for whatever reason, movies that we share with people. They're good movies, bad movies, blockbusters, forgotten indies. What matters is the reason why these are the films that stick to us, and there's no better conversation to have with another movie lover to get to know them.

Every week, I love having these conversations with my two friends. So first up, we've got my band leader, my old buddy, Craig Ceravolo. Craig, welcome. How are you, sir?

CRAIG: I’m doing great. How are you?

D: I’m, I'm very good, and I'm very excited about today. And we cannot throw this fight club without the Tyler to my Narrator. So please welcome my cohost, Aundria Parker.

A: Hello. Hello. Hello. I do look as good in the pink fur jacket just so everybody knows.

D: And I believe you exist. I do.

C: Spoiler alert.

D: Yeah.

A: Punch me!

D: Today, we have a very cool guest, guys. Today's guest wanted to talk about a particular year and a particular theme from that year. And so we're gonna roll it back to 1999 for this one. Aundria, how familiar with you, were you with these three titles?

A: Extremely familiar.

D: Excellent. And you, Craig?

C: Come on.

D: Yeah. These are these are big ones. These are fairly big title. Now, how about the extra title, though, that was sent in response?

C: No. And I can't wait to talk about it.

D: Okay. Alright. Good. Yeah. That one was a, that one is definitely what I think of as a hip pocket. That is a people do not know that until you drop it on them. Well, if you're ready to play, today's guest is waiting. They are what we would describe as Extremely Online. They are an author of some repute. They are well known for one website in particular earlier in their career and for a whole lot of very silly podcasting. If you remember our last guest, Allie Goertz, was for a brief time the editor of Mad Magazine. So today's guest was deeply connected to a well known humor website that shared a name, but no ownership or creative DNA, with the magazine that was for many years the primary competition to Mad. Would you like to guess?

C: Well, I'm going to go with Cracked…

A: Right.

C: Yeah.

D: Okay.

C: … as the website.

D: That’s… perhaps correct. We will see. I will say that today's guest started writing what became their first novel as an online piece of serialized fiction. They would publish a new chapter every Halloween, appropriately enough, under a pen name that they ended up using for many years. That novel became a movie that was made by one of the great cult horror directors. Would you like to guess?

A: This, this is so cool, and I have no idea.

C: I know.

A: Who is this guy?

C: Guest, I'm so sorry that we haven't guessed you yet, but we can't wait to talk to you.

D: Oh. Alright. Final one. Today's guest's latest efforts include frequent appearances on a podcast with an infomercial-inspired title and a TikTok account where their droll sense of humor seems to be reaching an entirely new generation.

C: Aundria, this is your world.

D: Since you guys don't have a guess, I'm gonna go ahead and introduce you guys to today's guest. Please welcome Jason Pargin to the the chat. You may know him as David Wong. That was his name for many years, but, of course, Jason now has, like I said, a huge TikTok account that has, I think, introduced him to a different generation of, of online kids. Jason, welcome. How are you, sir?

JASON: I’m doing great. People are gonna get mad at you. It is Pargin.

D: Pargin. I'm sorry.

J: It is totally fine. Exactly 100% of podcast hosts pronounce it the way you pronounced it. I have to correct it every time. I have a thing where, normally, I will email them in advance and let them know, and this time, I just forget that everybody does it.

D: No worries, sir.

J: Because I don't ever even say my name. Like, on my tech talks, I rarely say it in the rare occasion. When I do say it, all of the comments are is that how you say it?

D: I would assume you’d know.

C: I would have said it that way, Drew.

A: I'm a member of that club, too.

D: Um, Jason, for… just to, to fluff you up here for a second. You were, of course, the author of John Dies at the End and its various sequels. And I would say that your new book, I’m Starting to Worry About This Black Box of Doom, is one of the essential texts of the social media age. I think you nailed it, dude. I truly feel like your book is how it feels to live right now and watch the absolute batshit nonstop lunacy that is social media.

C: Oh, good.

J: Yeah. If there's anybody out there, if this is your first time hearing about this book, it's currently… it just came out. It's on in hardcover and audio and and ebook, but it’s, it just came out in September. But, yeah, the premise is basically that there's this rumor that goes around on the Internet that there's a domestic terror attack on the Capitol underway and that the authorities don't know anything about it. So you have, like, a bunch of extremely online people who join together to try to stop it, and it creates this ticking clock where it's like, can the Internet, the way it is, actually arrive at the truth of what's going on in time? And the answer is almost certainly not. It’s… if you've ever tried to watch the Internet solve a crime in real time and you see the way misinformation and hoaxes just bloom, well, here, it's kind of like trying to diffuse a bomb but the person trying to tell you what wire to cut is filtering it through, like, 4Chan. So it’s… it… that's not exactly what's happening. That is metaphorically what is happening. So it’s, it's this ticking clock thriller where a bunch of very online nerds all have very different opinions about what's happening, and so you kind of watch the truth struggle to find its way through this ecosystem. And if I've done it right, it is as maddening to read as it is to go on Twitter and try to track an election or an assassination attempt or anything else.

D: Well, I honestly feel like humor helps with this because it is so infuriating otherwise. To have this conversation seriously just makes me crazy. And I think what you do so well is… and it's that Strangelove thing… you're looking unblinkingly at the worst case scenario here, and you find the humor in it. And I think that's something that in your work, you know, John Dies at the End and that series… I think it's it's very much the way you leaven the craziest parts of what you write or the darkest parts of what you write.

J: Yeah. And that's just coming from a position of believing that the world is a ridiculous place. Like, even if… no matter what happens, even if we found out an asteroid was about to destroy the Earth in seven days, the, the way we reacted to it would be very, very funny. Like, there's not… it’s, it's fine to stop and acknowledge that every once in a while. It’s, it's a coping mechanism. So I, you know, I, I try to… I'm not out to to depress people. I see the world that way. I don't think it's improper to see, like, dire situations… I think if I found out I had a terminal illness, I would be joking about it right up until the last day because that's honestly the only way I know how how to live. My brain is just broken that way, and so I, I have spent my career trying to make the rest of the world, like me, broken.

A: Your brain has evolved that way. Yeah. Not broken. Not broken at all.

D: Well, Jason, I will say that you are so far, out of our guests, the one who picked their films the fastest. It seemed very quick, a response, and you immediately tied them together, and there was a a common link, which is clear as soon as I say the three titles. Tell me why you picked today American Beauty, Fight Club, and Office Space.

[a medly of the American Beauty, Fight Club, and Office Space trailers plays]

J: Well, these are three films that, if you were around and an adult in 1999, which all of us were… I don't know how young your listeners are… there was this… there was this narrative of these movies. This is the year that all these movies are nailing what's wrong with, like, like, the cultural malaise among middle-aged white men in the United States. Some people would throw The Matrix on there, but knowing who created that film, I think it's a little bit of a different narrative. But at the time, it was like, yes, that's what this is about. It's about how cubicles are a prison, and they're robbing us of the true meaning of life or whatever. So we had these three films that, at the time that I watched them, it was… you know, because you do the math, I would have been in my early 20s back then, would have been around 23, 24… and it was, like, oh my god, I can't believe what I'm watching. Yes. This is what’s… this, as an angry young male… yeah. The, these movies have nailed it, especially Fight Club.

Now watching them, 25 years later, it is unrecognizable what I got out of those movies at the, the time, the person I was at the time, where the culture was at the time. To the point now… the reason I brought this up, there's a meme that goes around on Reddit, like, once a month, where it's a screen grab of… it's like a collage of all of these miserable cubicle dwellers. You know, Peter from Office Space and the Narrator, the… Jack from Fight Club, and Lester from American Beauty. And it's like, oh my gosh, how miserable that I have this high paying, comfortable office job and and a love… and a beautiful apartment and a lovely home. How awful that would be to have all of those things. And I… it's clear that Gen-Z and even people that are maybe a little bit older are so detached from that world because that world feels like 100 years ago.

D: Yeah.

J: Because when 9/11 came along two years later, it totally changed everything about the culture that those movies were talking about. So now they just look ridiculous, and not just because of the Kevin Spacey aspect that, that the… American Beauty might be the… set the all-time record for the film that has aged the worst in the history of cinema. So now I can go back and watch them and… still, you know, Office Space is still a fantastic comedy. Fight Club is still a gorgeous piece of filmmaking, but the meaning is so profoundly different that you can almost chart how my life and the culture has changed by what I thought of those movies at age 23 and what I think of them now.

D: Well, I’m, I'm a little bit older than you. I was 29 when all of this came out and working out here. And so a lot of these were movies that I watched parts of the production of or that I was aware of as they were in production. Like, I remember Fight Club. I was on the set for The Green Mile, and a lot of the crew there had just come from Fight Club, a lot of the, like, below-the-line craftsman, the set builders, things like that. And a lot of them had walked off mid-movie, and the buzz on the set of The Green Mile was unreleasable. I don't know what they're doing and neither do they. That David Fincher guy is out of his fucking mind. That movie's terrible. And they were just they were, like, angry that they had wasted five or six months of their time on this thing that they utterly did not get. And I had already read the script, and I had this very strong response to it, so I would listen to that and try to imagine, is it out of control? Is it… did it not work? And, and I remember that first screening I went to on the Fox lot. As soon as that Dust Brothers score kicks in and you start to move across the brain, I'm like, oh, they're wrong. They're wrong. I know they're wrong. Here we go. I think he did it. And what I loved about it then was the satirical aspect. I didn't believe in Tyler. I thought Tyler was a cartoon, but I think I had just that little bit more life experience, where as soon as it came out and the response started to come back that people were identifying with Tyler and really not listening to the second half of that movie, I… I'm fascinated. Immediately, it became a different film because you started to go But how? I saw this movie. How did you see that movie? And I do think it's a matter of a few years, especially right then.

J: If anything, it was punished for coming out ahead of its time, because it, it was not a hit with audiences. A lot of people lost their jobs because of this movie. Very high-budget box-office bomb. They had very difficult time selling it, it was clear. It's more relevant now, but I think people would miss the point just as badly, because now I view it as the best film about cult indoctrination ever made.

D: 100%. That's why I show it to my… I've shown it to both of my sons on their 16th birthday as part of a a wider group of films that I've shown them about programming and about how young men in particular, you are pushed all these different ways. There are all these things that are trying to program you and how easy it is to hand yourself over to it. I showed that with Full Metal Jacket and a couple of other films. And I do think Fight Club is one of the best movies about the way that works and about the seductive side of how people get indoctrinated.

[clip from Fight Club plays]

D: It has to be sexy. It has to be appealing if it's going to really pull you in. Right?

J: Yeah. Because it demonstrates its point by indoctrinating you, the viewer, because it starts… this is the exact steps that a cult will use, where it starts out with complaints that nobody can argue with. Are you tired all the time? Do you, do you feel like your your job is running you ragged? Do you feel like your work doesn't affect… it's not good for anything? You're not bringing any good into the world? Do, do you get depressed looking at your future? Do you feel like everything you're fighting for is meaningless, just to get a slightly better sofa, a slightly bigger TV? It's like, yeah, yeah, yeah. Like, do you hate your boss at work? You know, is he kind of a jerk? Do you hate office corporate culture? Yeah. Yes. And you're nodding, nodding, nodding. It’s, like, hey, you know what we ought to do? We ought to burn down all of society and live in in a commune. What!? It's like, oh, okay, so you, you went from a series of sensible complaints and you got me nodding along with it, then you gave me a very handsome and charismatic man who has… says a bunch of cool, memorable lines and quips and has these things that sound very profound and this cool soundtrack that's hypnotic and makes everything you're watching look beautiful and cool and it's fast and just… it makes you feel like you're smarter than everybody else because it's like, hey, we recognize that advertising is shallow and stupid. Not like those sheep out there. Not like all those people. We are part of the the elect super-smart whatever. And then after you've bought in, it's like he takes away your name. You, you… takes away your individuality. You're all made to dress the same. You're all shaving your heads. He's robbed you of all of your power, all of your initiative, all of that stuff you claimed you were missing in life. He's turned you into cattle. But you can watch a generation of young men who had that Fight Club poster in their dorm…

A: That's exactly right.

J: … who thought, yes. They're, like, quoting Tyler, like, yeah, I stopped watching it halfway through because I figured, like, I figured out… I had the idea. You know? Pretty much this is gonna be more of that. It's like, no, the whole back half of the film is David Fincher trying to dismantle every single point he makes. It is, says so much about programming and how this stuff works that people just don't remember that part.

D: I can ask you, Aundria, because… it's one thing for young dudes who saw that movie and had it land on them… that movie is so hyper over masculine, and everything about it is about masculinity and masculine body image and everything else…

A: Yeah.

D: … so what was your initial response to it? Because it’s, it's a giant fucking crazy thing of a movie to happen to anybody…

A: It is. And I saw it. So in '99, it was my freshman year of college. I was…

D: Okay.

A: … and like John said, or Jason said, it was… I was, like, what am I watching? This is the coolest movie I've ever seen. It's so edgy and different. Oh my god. It looks so cool. Who's David Fincher? Like, all of those things. And you and… you're, like, wow, it's really telling some truth about the way things really are. Right? And, you know, all of that stuff. And then, and then it became basically an incel playbook. Like, it just, it, it was… that's just what it became. If you had… like you said, if you had that poster in your dorm room, it, like, even by, like, 2007, 2006, you're, like, oh, your favorite movie is Fight Club? Swipe. It was just… it was like a red flag. It was a warning sign. Yeah. But when it came out, it was not that at all. It was so different. It hit like a sledgehammer to the gut because it was different. And it was based on a book that had a very small cult following. People didn't really know about it. So it just like… it was a flop, like you said, and to watch it as a woman… it's hard. It's hard to say. I, I… obviously, it has a certain appeal to it, visually, you could say, for most chicks, I'm sure.

D: Well, let's put it this way. I think on the Kinsey scale, I moved while watching this movie. Like, I, I… my number may have shifted on this. Brad Pitt is insane in that movie.

A: He is.

D: He is a physical specimen, and I think it's the first time he'd ever done that to himself, where you look… you don’t, I don't understand how… how did he turn into that?

A: There's, like, a ferocity to it that was very appealing, and I've never been a Brad Pitt girl ever. But I was a huge fan of Edward Norton. So that was the draw for me. Huge fan of Edward Norton from Primal Fear and everything. But, yeah, I do, I do remember that feeling of watching it and being really wide-eyed and just, like, this is… and it's a, it's a, it's a common theme through all three movies that Jason picked, too. It's like, I have never seen a movie like this. This is so different and cool, and, and it's odd… not odd, I guess… but the way that time changes things. Like, two years later, we had 9/11, and the entire culture that was in those three movies was kind of null and void, just like that, in the snap of a finger. And now, 25 years later, they seem almost quaint in their, you know, in their edginess and their, you know, in their fortune cookie dialogue and the stuff that Tyler says and, like, you know… it it was a trip rewatching it, for sure.

D: Was it a theatrical one for you as well, Craig?

C: Yes. I was 25 when it came out. So that gives you an indication of… I was right in the zone for it.

D: Yeah.

C: But, you know, the thing is, I didn't grow up, you know, I didn't grow up with a lot of money. So that… I always remember that scene where he's picking out the IKEA stuff and how he's making fun of it. I just remember even at 25 going, well, I kinda want all that stuff. Like, that didn’t, that didn't appeal to me of this, of this… I was very much like, I didn't shun the materialistic aspect of it. But I will say in… you said, and you just said it... this is what I was thinking of, Drew, when you were saying, is that it's very homoerotic in a great way, like, in a in a wonderful way that… I don't think that we know as young men how to deal with that attraction that we might have, and it really does… I remember being in college before Fight Club came out, where we would just get in weird fights, and we wouldn't know why. Like, we would be having physical fights with my roommates. And it wasn't anything weird other than I think that we had this… this is gonna sound insane. We had this, like, affection that we didn't really know what to do with it, so we just started punching each other… that I really, I really gravitated towards that.

D: We definitely came from a generation that was not ever… there was no physical touching another dude. For any reason. Under any circumstance. It just wasn’t… I, I grew up in the South a lot, and I, I, I certainly… I, it was…

C: Hey.

D: … it was a weird time to grow up, man. It was still… there was a lot of panic. I, I look at my kids now and they have the ability to be physically affectionate with their friends in a way that I envy. Like, they have zero hang-ups now.

C: I do, too. Yeah.

D: But, yeah, if you're gonna imagine a version of yourself that you idealize and you're Ed Norton, Brad Pitt is is exactly right. That movie could not be cast…

C: Beautiful.

D: … any better. And it's the fact that he's funny and the fact that he looks like that. It's that combination that makes Tyler Durden so insanely winning.

J: What you guys mentioned there is… cannot possibly be overstated, because I feel like even 25 years now, on… 25 years later… we have a clear idea of what it means to be touch starved, that people need physical touch to survive, and that boys, at least in the generation I grew up in, we did not touch each other unless we were fighting. That's the only chance for physical contact you get. And I even, like, the… even seeing people, like, review the movie and talking about how, oh, it's secretly gay. They're all having gay sex with each other. It's like, no. No. See, that's what I grew up with. If you touch another man, it means you're gay. And here's the thing. Try watching any kind of a fantasy or action movie aimed at men, something like Lord of the Rings, and notice how much the characters hug and touch each other.

D: Mhmm.

J: It's not gay. It's a fantasy of, wow, they're allowed to hug each other and to cry into a guy's shoulder over the, you know, the tragedy of their mentor dying to a giant mine demon.

D: The last half hour of Lord of the Rings is just hugging. I, I think… absolutely.

J: And there's a sickness among young males that is as much of the fantasy as slaying the dragons, and we never talk about it. And Fight Club touched on this. It is not overt in these men bursting into tears after their fist fight. It's like, yeah, they're… this is the only real therapy they've ever had. And this is the, the… it was only allowed in the pretense of combat because that's the only time you're allowed to to do it.

Ed Norton: Every week, Tyler gave the rules that he and I decided.

Brad Pitt: Gentlemen, welcome to Fight Club. The first rule of Fight Club is you do not talk about Fight Club. Second rule of Fight Club is you do not talk about Fight Club. Third rule of Fight Club, someone yells stop, goes limp, taps out, the fight is over. Fourth rule, only two guys to a fight. Fifth rule, one fight at a time, fellas. Sixth rule, no shirts, no shoes. Seventh rule, fights will go on as long as they have to.

And the eighth and final rule, if this is your first night at Fight Club, you have to fight

C: I was just gonna say, I wanna retract using homoerotic. But, you're right. It's not… it doesn’t… that's just the only way I knew how to place it…

D: Yeah.

C: … and you're right. It's not that.

D: It's definitely… Fincher shoots, he shoots all the, he shoots all the guys during the fights as Greek art. Like, he shoots the muscles, and he’s… Fincher is very aware of what he's shooting, and Cronenweth… it was shot… Jordan Cronenweth, who shot the movie… it's sensational. It is a beautiful movie.

C: All surface.

D: Yeah. All surface. And I think he is very aware of the rot of that world versus the beauty of the people in front of it. And I… there's no accidents in any of the imagery Fincher's using. It's meant to seduce you. And young men 100% responded to it, which is absolutely worth interrogating. And I think it still works. My boys definitely had the same response, where the first half of that movie is all acceleration of, oh my god, I'm feeling this. I'm feeling this. And thankfully, I think I had shown them enough satire and enough dark comedy and enough things that prepped them for the shift in the movie to where they realized, okay, something's changed, and I'm not hanging anymore. I'm not identifying anymore. But I, I think it is the, the surfaces of that film are so seductive. And, Jason, I, I've heard you talk a little bit about this, and I, I really, I didn't connect it to Fight Club, but you're right. I think it's a powerful part of what Tyler offers Jack is an excuse, a reason for this contact, and a place for it to happen.

A: And he's using, the Narrator's using the support groups in the beginning of the movie..

D: Yeah.

A: … as, as that same reason, that same out, that same let me hold you and let me weep. Any…

D: Yeah. It literally opens on Bob and him crying.

A: Yeah. Right.

C: Mhmm.

J: Right. Because only in the context of people who had terminal diseases were these men allowed to cry. Because that’s, that's only something, to that extreme…

A: Extreme. Yeah.

J: … where is, if he just wanted to cry over the fact that his life is hollow and meaningless and his work is hollow and meaningless, everybody… nobody would want any part of that. That's unattractive, and that’s, that's effeminate and weak or whatever. And the movie does not state these things as overtly as maybe as it could, but this is a movie that cries to be remade if a studio wanted to go bankrupt again, because all of this… remember, all of the stuff he's talking about, about the pressure… because the whole thing with buying all the IKEA furniture is the pressure of trying to maintain an aesthetic in your life. It's like, this was before Instagram…

D: Yeah.

C: Right.

J: … this was before the concept of having to build an aesthetic that you can have in the background of your visual social media was a thing. Like, everything this movie talks about, you can multiply times 100 to the point that looking at Tyler Durden and seeing an Andrew Tate…

D: Yeah.

J: … or one of these modern young male influencer types who's all about, like, being surface level tough, you know? It’s, it’s… you know… and kind of, they have a house that they can trash if they want to. They're, they don't care about your rules. They're very conservative, in that we should just let the disabled people die. It should all be, you know, survival of the fittest… like, all those talking points, if you made them would be today, you’d say, oh, that’s… they're, they're doing an Andrew Tate parody. It's like, no. This was a quarter of a century before he came onto the scene. All of it makes more sense now. You just update the names of the technology that everybody's using. But the invention of the smartphone… everything they talked about in the film is ten times greater, including the indoctrination pipeline, which is… now you can run it… start on YouTube, and you'll get sucked into some influencer, and then they will start slipping in some right wing ideas. And, and it all starts with, aren't you frustrated with this job market? Isn't it frustrating that rent is so high? Isn't it frustrating the pressure you have to try to get married? Well, what if I told you that society has lied to you and that your wonderful masculinity is being suppressed? The true way you express it is by buying my merch…

D: Yep.

J: … and repeating all of my catch phrases everywhere you go, by mindlessly repeating things I said, then you will truly be a strong, brave individual surviving against the oppression of whatever, the feminist, whatever.

A: I mean, the term snowflake came from this movie.

D: Yes. It did.

A: And, Drew, to your point about your boys knowing satire, you know, dark comedy, this movie, kinda like The Matrix, too, is a perfect example of a lack of media literacy. What happens when you don't know how to interpret a film other than looking at the movie and seeing it with your eyes? You know what I mean? It's a, it's a perfect example. Watching how “red-pilled” got taken from The Matrix and, and…

D: Yeah. Literally watching the Wachowskis argue with people about you're using that wrong. I, I created it.

A: Yeah.

D: Okay. Well, yeah… and I, I think both Lana and Lily are very aware of the fact that once you… and I think Fincher's the same way, I think… when you release something into the culture, you don't control it anymore.

A: You can argue for it. But…

D: … and we are increasingly reaching a point where you have no idea how it's gonna bounce off people who don't dig into a text or a subtext. It's fascinating. I… so, this next film…

A: So scary.

D: … yours, your second movie, Jason, I had not seen probably since 1999. And at the time, it was kind of important because, you know, the early days of the Internet were all about respect. It was all about those moments where the mainstream finally paid attention to what you were doing on the Internet. And for Ain't It Cool, the early days were always marked by studios ignoring us or cursing about us. And we got a phone call in March, I think, of '99 from somebody at DreamWorks. And they asked Harry and I to go to DreamWorks to watch a rough cut of American Beauty. And they hadn't shown it to anybody yet. And we watched it, and we really enjoyed it. We had very strong notes for them.

And they felt like that was this moment where they were asking us, is this something you guys would even like? Like, we don't know what you like. We truly don't get you. So here's what we are doing this year. This is, we think, our biggest movie. Do you like it? And we loved it. And so they went, oh, okay, well, you're not insane. We can talk to you. It was a real turning point in terms of studios actually talking to us. And then the movie became this much bigger thing. I think it's wild looking at it now that that is the film that won Best Picture in '99. Out of all the movies that came out that year, that could have been part of this, this conversation, that's the movie that won.

A: I feel like a lot of the movies that came out that year, even if they were not successful in the box office or, like, among awards chatter, all had these second lives on VHS, specifically, or the added end of DVD, specifically Fight Club, Office Space for sure, 1000%.

C: Yeah.

A: So a lot of these movies now that we consider cult classics from '99, people think are… younger, like, the younger generation might think they were huge hits. Everyone lining up at the theaters to see them, and they weren't. They were just, like, well, it's Friday. We have to rent something. How about Office Space? Or it's Friday. We have to rent something. What about this Fight Club movie? So the conversation… the way we look back is so different on the popularity of the movies at the time…

C: I understand why you're looking back… The Matrix off of this group, clearly… but, god, it really does fit right in if you look at it just in the, in, in a, in a capsule.

D: Mhmm. Sure.

A: … or the, the white hat of this kind of group of movies, though. It's kind of the one that's been able to prevail even though it had maybe… I’m, I'm sorry…

D: Maybe it's helps that Matrix was science fiction and that Matrix… I, I also think it's the fact that it became a franchise kind of made it its own thing that stands apart. These other movies, as a standalone… American Beauty is such a singular weird thing. And rewatching it, it's hard not to, in some ways, be icked out by the Kevin Spacey of it all. And this is, I've gotta say, the Kevin Spaceyest that he has ever been. He is so in command of the withering sarcasm, the sort of seething contempt. Like, all the things that were making him interesting throughout the ‘90s kinda come to a head here. And it's fascinating to cast him, and it's fascinating that Alan Ball is the guy who wrote this, because this is a heterosexual midlife crisis. Lester is straight and supposedly cis, and it, it’s… but it is such an odd movie because there is the next-door neighbor stuff. There is all the subtext of… again, what we're talking about, it's still a moment in 1999 where a character like Chris Cooper didn't feel outrageously outside of the culture. He still felt like he was somewhat speaking for a section of the mainstream, even with the language he used. Watching this now is a very different experience. I, the stuff that's funny is funny, is very funny. The stuff that is gross skeeves me out so much more at 54 than it did when I saw it at 29.

C: How do you think I feel?

D: Oh, yes.

C: I have teenage daughters.

D: Yeah. Yeah. But so it’s, it is fascinating to look back at. Your response to seeing this again, Jason, in terms of how it lands for you now, what was this film then and what is it now?

J: I don’t, I don't know if the young people out there… again, I keep acting like you have a lot of teenage listeners. I don't know if you do or not. But, one thing that I… I don't think young people realize how huge of a deal American Beauty was in terms of it was on magazine covers. It, it was… again, it swept the Oscars. At least it, it felt like it swept all the major awards. Critics talked endlessly about this film as an all-time, like, landmark achievement. And I remembered watching it and feeling like, I guess… I don't feel the right type of middle age malaise he felt, but I absolutely watched it as I'm seeing one of the great films ever made. It's one of those things where I’d… I wasn’t, like, you saw it before anybody else. I saw it in the context of…

D: Yes. Oh, it was hyped.

J: … yeah. Every frame of this film could be hung on the wall as a painting. It is everything… every aspect, every performance is fantastic. So there's no objectivity, the way… if it'd been something you just ran into on cable one day, and, like, I'll try… I like Kevin Spacey. I'll watch this thing. No. It, I was seeing it in the context of this movie is not good. It's important. It will change your life. It defines the culture. The… to see what a time capsule this film is, for example, the, the neighbor kid… is it Ricky?

A: Ricky.

J: … like, he has this extremely weird personality quirk, which is that he keeps a video camera with him all the time and randomly just shoots aspects of his life, which is treated in this film as freak weirdo behavior that defines his whole personality. Because can you imagine having a camera on you all of the time and just, just filming random moments of, like, the meals you ate or just filming some weird thing in the park? Like, oh, this is a pretty little trash bag or I like this plant or this tree or this squirrel. Can you imagine what kind of a weirdo pervert would just be filming? Like, to just always have a camera with you? And that's treated as, like, the sign that this kid has totally disconnected from the world because his psychology is that the camera gives him distance from the world, this world where he's miserable and he's got the abusive father. But when you look, look at it through a camera, it lends an unreality to all of it, and that kind of, like, gives him some sort of a perspective.

[clip from American Beauty plays]

J: So now you have a culture where 100% of the people have a camera in their pocket at all times, and everyone films their meals in… to the point now that I think if I showed this movie to a teenager, I think they wouldn't get what's going on there. Like, why are they treating him as a creep? And there's this whole speech where she talks about, like, don't you feel naked being on camera? Because it's such a weird sensation. Like you step outside your door, you're on 36 cameras now. It's that… that feeling is gone. They're, they're pervasive. And that happened really fast. 25 years ago is not that long ago.

D: No.

J: But this feels like a movie from an alternate dimension.

D: I think, I, I, I agree that that stuff, the… and it's the last moment really before any of this exists. 1999, as a flashpoint year… even in the moment, we knew something special was kinda happening, but I don't think we realized it was the closing act on, sort of, independent American cinema the way it was before the 2000s happened. And, as you said, 9/11 broke culture. It, it broke everything. It broke the film industry in a profound way. And, really, culturally, we've never recovered. I don't think we've, we have the same… there was an abandon to the ‘90s. The ‘90s were like the best of the ‘80s and the best of the ‘70s jammed together. It was all the slick of the ‘80s, but it was all of the independent spirit of the ‘70s. And it felt like they kind of figured out how to marry the two.

And this movie feels like a studio saying, we wanna make the biggest indie film of all time. Like, we wanna make the ’90s indie movie, but at a studio level. And that's really how American Beauty plays to me when I look at it now. It feels like it's very much in conversation with all of the independent filmmakers that were working, who were telling these personal stories and talking about things that were happening. Studios in the ‘90s were very slick and very corporate. A lot of the studio product is product in the ‘90s. So this does feel like DreamWorks taking a step towards some hybrid of the two. And I think that's part of the reason that it got embraced on such a big level was, oh, we can do this too. We can make this kind of movie. And I feel like that was happening at a lot of the studios that year. Fight Club is absolutely them going, well, the fucking creep that made Se7en… I mean, he's crazy, but something happened there, and we don't totally get what it was. So let's see what he does with $75 million. And, you know, I, I feel like the, this movie… if Spacey wasn't in it, I don't think it would change how active it is in our pop culture. I don't think it would hold a bigger place. I think it is more of its moment than almost any other film that year, which is not out of line for what wins Best Picture. Frequently, I think the Oscars are the story that Hollywood's telling about itself at that moment. And so that film that they pick is kind of a snapshot moment of this is who we are. This is what we stand for. This is what we believe in. And I feel like that's the studio saying, look, we can do this too. We made this kind of movie the way you guys did, and we don't have to give you the awards anymore. And there’s, there's something about that studio, the studio kind of… this… that when you watch the movie now, there is a very slick kind of plasticky thing to the whole movie that I don't think you get from a lot of the ‘90s indie stuff. This feels very calculated. And I don't mind that with some of the performances. I think Annette Bening knows exactly what movie she showed up for and walks away with it. My favorite performance watching it now, undisputedly, is Annette Bening. I think she’s… whatever movie she's in, I want four of those. She's fucking amazing. And her response to Lester is 90% of what I love about the film now.

[clip from American Beauty plays]

D: Lester is not a character that I feel any identification with. And I thought maybe watching it older, maybe there'd be a lit… no. I just don't. I think of Lester as the same thing as… I think of the, you know, the guys in these other movies. He’s, there's a very young, emotionally immature thing to… I wanna just have no responsibility, and I wanna be this, and I wanna be free, and I wanna… it's an immaturity that Lester embraces. And I think the film knows, knows that. I don't think he's the hero of this movie at all.

J: And I think that all three of these films had that in common, and that you have protagonists who will say, I'm upset that, like, my masculinity is being restrained or that, you know, I, I'm not… but then you look at their actions, and what they want is to be teenage boys again.

D: Yes. Yes.

J: That's the same with Fight Club. Like, the whole, the whole appeal of Tyler, Tyler's organization is you're gonna live in, like, that apartment some of you had when you were 20, living with, like, six other people in some house that you were slowly trashing where you don’t, you're not paying property taxes. You're not having to, you know, obey a dress code at work. You can just tell everybody to screw off. You're not having to save for retirement or anything like that. It's not, it's a version of masculinity that’s… it's just… people wish they were 16 again. So here, I feel like now it very clearly is curing this guy, that it's like you have everything and the way you're trying to rebel against the system and, and you even, you know… there's this shot from the film where I think he's writing code on his screen and is projected against his face, and it looks like prison bars. Like, this, this cubicle is his prison. This, this, you know, $200,000 a year office job, working in the air conditioning every day…. it’s hell. This is the worst hell you can find yourself in. Oh. That his, the thing… and, and, of course, you know, he quits the job, then he, like, buys a muscle car, and he, and he starts working out in his garage, doing stuff that a 16-year-old dude does. And that… yeah. It is trying to criticize him and then whole… his whole thing with lusting after, you know, his daughter's friend in, in high school. That movie being made at that time doesn't see that as predatory. It sees that as just an extension of he wishes he was 17 again. Like, he wishes or, or he missed out on that stuff when he was 17.

So, him… you know, I, I, I don't think that's out of line in terms of, you know, the… there's an… you may not know this, but there's an entire category of pornography that's, like, 35-year-old women dressed as Catholic schoolgirls because that's, like, this hot thing where… and I think some of that is just 40-year-old dudes who wish they were 17 again. Like, I don't think they want to go out and molest a school girl. I think they wish they had that life again where they're going out on the weekends and drinking, and there's no job to be at. And you're just, you know, you're just out there, and you, you weighed less, and you were, like, the sexiest you would ever be. And it's like, man, I see pictures of myself. I thought I was ugly back then, but, man, compared to the way I look now, I was, I was hot. So the film trying to say in the… it's at the very last moment when he's about to violate this young woman, it suddenly hits him. Oh, she's a child, and I’m, I'm an idiot. I think at the time, that was actually revelatory for a lot of people who realized, oh, this is why my fantasies are so wrong. Like, he's not seeing her as a human being. He's fetishizing a youth that he misses or never had.

D: Yeah.

J: Now if you make that movie, the aspect of the power imbalance, the age imbalance, the fact that he's taking advantage of an inexperienced, you know… like, it's you, you're not sympathetic to him at all.

D: Well, I think the conversation has changed, thankfully. I think culture shifted. This is a case of a movie where literally when it was made is the only moment it would be made. And the culture is 100% changed to a point where Lester can't be ignorant of any of the other things that are going on here. In 1999, I do think the culture still was at a point where they they're not even excusing it, but the ignorance is real. Like, there is a cultural ignorance of these dynamics that has not been discussed or really dissected yet. So Lester is clueless about his own behavior. He really doesn't get how predatory he is.

J: To the point that I think the film even somewhat, like, gives him a pass on the idea that this 17-year-old or how old she's supposed to be is extremely sexually experienced and that she's the predator and she's coming after him. Like, that's a fantasy that you would not put in a film now, because you wouldn't buy that this guy that age doesn't realize that she…

D: Yeah.

J: … is a child. She has no idea what's going on or whatever she says. Like, you don’t, you don't see her. But, again, in 1999, I cannot emphasize there were rock songs that were straight up about, like, wow, the 16-year-old is hot.

D: Yeah.

J: I’m gonna, I'm gonna bang these schoolgirls because that's, like, the sexiest thing you can be is 16. This… thank God that the world has changed a little bit.

D: Incrementally. But yes.

J: So the… in terms of, you know, with… I think the premise of this show is that these are films that we kind of go back to and holds a special place in our heart. American Beauty means a lot to me just because of how it is a look into a window of a world that… it doesn't feel 25 years ago. It feels 50 years ago. It feels 75 years ago. Like, I don't recognize anything about that culture, including how they treat marijuana as this weird, mysterious drug that only select few weirdos do. And the movie's not quite clear on how much it is supposed to cost or or how, or how you buy it.

D: And even how much they disagree with it, like, it’s… is it funny that, like, is it, like, the movie doesn't really have an opinion. It’s… yeah. I find this one to be the the one that I had the, that really the, the most to chew on watching it this time because of how different it felt. Whereas when I put on Office Space, it was like a warm bath.

[clip from Office Space plays]

D: I think Mike Judge is a treasure. I think Mike Judge is one of our genuinely smartest American humorists for that last half of the 20th century and the time since. Because, boy, he knows how to pierce without condescending, and he is sympathetic while at the same time acknowledging every quirk and fault that anybody has. I, I look at King of the Hill or I look at Office Space, and I really am blown away by the empathy that exists in his comedy while at the same time, never dialing down the the humor. Like, it’s, it's not the overly kind thing that I think Mike Schur does. Mike Judge still has an edge to him. Mike Judge still has some anger. Office Space is as angry as Fight Club. It's just fucking funny, too.

J: And he does not spare his protagonists any of that criticism. Because at the end of the day, again, it starts out with a guy who's miserable in his, in his comfortable office job and his neat little apartment. And it feels like he is the most oppressed person in the world. And he simultaneously mocks the just absurd carnival of madness that is corporate America and the, the bloated middle management structure of these companies, whereas the whole deals where he's like, I report to five bosses. Like, it's not even clear, you know, who I report to. And if I make a mistake, I hear from five different people who don't all talk to each other. And being stuck in the middle of that and the soul sucking nature of that, that's all nailed. But then when you ask him, well, what do you wish you're doing with this life? His answer is not, well, I wish I could go solve real problems. I wish I could go volunteer with the homeless. I wish I could take care of my my sick mother instead of having to spend all my time at this soul sucking office job. No. He wants to do nothing. He, he wants to stay home and watch, and watch reruns.

A: Yeah.

J: And, you know, he… again, Mike Judge inserts a, a, a foil framing on Jennifer Aniston's character who, like, confronts him in the car because he’s, he's, like, telling her, well, you know your waitress job? That's just like the being a Jew in Nazi Germany. She's like, what? Like, I would just get a different job if I… it, it, like, these things are annoying, but don't compare our situation to that. Yeah. Like, you, you… again, you want to be a child again. You want to not have any responsibilities. You want to have a room and a TV and somebody else paying the bills, somebody else going to work every day. And so the way this guy is rebelling against this objectively absurd corporate structure and corporate life and culture is he wants to go back to being a kid. So he, he… it is such a subtle bit of satire that, again, this totally bombed at the box office. They didn't promote it. It found its life… I saw it on Comedy Central. Like, I did not see this thing till it was on TV. But once it was on Comedy Central, they were shown, like, four times a day seemingly. Like, it found its audience, and it was then that my coworkers started quoting lines from the movie, not when it was out…

D: Yeah.

J: … that when it was running on cable four or five years later, because more and more people have that type of, you know, open office plan cubicle job than even in 1999. So, like, that life, those archetypes, the people have, like, the very petty complaints, like the guy with the stapler. You know, a lot more people would go to work in offices and and get to know all of these things in the office, the, the tragic, like, office birthday party and all of those things are in the movie. Everybody, like, more and more people would identify with that. I think a lot of people do miss how harshly he is judging the protagonist whose happy ending is he gets a… he does, he gets a job where he's doing real work. I mean, he gets construction jobs, so he can actually see some results of what he's doing. He can see a job site getting cleaned up or he can see something getting built, which is what he was missing. Because the whole reason he was miserable is because he didn't even know what his work was for.

D: Mmmhmm.

J: Like, he was generating these reports and then forwarding them up the chain, but he doesn't know if anybody's doing anything with this information. If so, what are they doing? Who out there is being helped by this? So that's the lack of meaning in his life. Because if you, if you had a job painting houses, at the end of the day, you have painted a house. It looks a hundred times better. You can drive past that house every day and tell your wife or girlfriend or whatever, hey, I painted that. Look at that. Look how good that looks. It's something tangible where the whole point of his, of his situation is he generates these reports. It's not even clear what they're for, what they're accomplishing in the soul sucking nature of that. But he does not go easy on… because, again, his group of friends, their whole deal is, oh, we are so much smarter than, than our our idiot bosses. We're so much smarter than the corporation. So they come up with that scheme to steal money that's like, oh, they'll never notice. And then it immediately fails because it's like, oh, no, you actually are not smarter than your bosses. Everybody here is an idiot, including you. This, this thing where you sat there in your cubicle and thought, well, if I was running this place, you know, it would all finally make sense. You know? They're not taking advantage of, in, of my genius or whatever. And it's like, no. Actually, you're not competent either. And that's a very Mike Judge way of looking at the world. He is much more conservative than I think a lot of other creators in Hollywood, but not in the stupid way that conservatives…

D: Not in a cruel way. It's not… it's not about cruelty or anything else. It's just genuinely that's who he is.

J: And it's genuinely about, like, taking some personal responsibility because that's the happy ending. It's not that they overthrew the company and made off with their millions. It's finally growing up and saying, look, if I want a different job, I've gotta go get, get a different job. Like, nobody's gonna do that for me. And in the end, that's what he does.

D: I think all of us, especially if we work in the creative fields, there are a lot of jobs that you end up doing over the course of your life. I was definitely raised by a dad whose… the whole thing was whatever job you do, do it like it's the most important job you'll ever have and give it 100%. And so I've really always had, I think, a fairly decent work ethic. And I've worked movie theaters and video stores, and I worked as a caddy for a while when I was a kid. And I've worked, you know, I've done a ton of office jobs when I moved out here. And, really the only time I didn't do well was my last office job when I started to get short-timers syndrome. I started to get this idea. I was working for the Director's Guild and I was working for the Assistant Director's Training Program, and I was supposed to be handling all of the applications for a year. And I was, at the same time, working on a play and getting ready to go rehearse this play. And I was, like, I was one foot out the door. And I think for four months, I just took everything that came in and put it in a desk drawer and didn't do anything. And then left in a huff one afternoon, like, I'm out of here. And I left, and it was chaos when I left. And I thought, that's it. I'm never gonna see this person again.

Years later, I'm at the New Beverly, and there's a screening, and I come out of the screening and I see Joe Dante, who I'd worked with. And I walk over, and I'm like, Joe, what's up? And he goes, hi, how are you, Drew? I don't know if you've met my girlfriend. This is Elizabeth Stanley. It was my boss from the Director's Guild, who I had not seen since the last time I savagely screwed her over and walked out the door. And it was the worst feeling I have ever had because Adult Me had a moment of, oh, shit, I have to… oh, I have to apologize to you now, and I have to mean it because I, I was so bad. And I look at this, and Mike… he nails it. It's the, there is this infuriating attitude that you have at a certain age that none of this matters and I, and I don't need to do it. And, and it's hilarious. And, again, perspective is a real son of a bitch. I look at this movie now and, I don't see myself in these people. I did when it came out. I 100% felt like I was in tune with them and, you know, I felt the same kind of anger towards all the jobs that I'd worked. And it's ridiculous. You know, it there is a ridiculousness to it. All the middle management stuff is maddening and real. And he observes that beautifully. I think, oh, God. Gary Cole in this movie. It's such a good performance. And he does such a good drone to it. I also think Ron Livingston is perfect casting because there's something kind of lumpy and not quite leading man about Ron Livingston. And that's not meant disparagingly, but he's a perfect best friend in a movie. You put him in the lead and he's a little undercooked, and it's perfect. That's exactly who this guy is. I, I, I wanna ask you, Craig, I know that you've worked a ton of jobs over the years, like, you know, to support the work that you, the work that you wanna do. You're creative. A movie like this, how does this one resonate with you?

C: Well, I haven't worked a ton of jobs. I've worked the same job for thirty years.

D: Oh, wow.

C: The same office. I, I work from home now, which, which is, like you just said, I really did associate myself with this at the time because I was working at that company, the same company I'm working for now, at the time. And, and I did have the version of TPS reports that I had no idea what I was doing with them. It was actually a couple of years where I was in charge of invoicing, and I could do it all on a Friday afternoon between noon and four, but they didn't know that. So I spent four days of the week surfing the Internet and downloading songs off of Napster.

A: Oh my god. That is incredible.

D: Yeah.

C: But now, you know, I'm, like, the… in charge of the… like, I have to make sure everything's running correctly. So…

D: Yep.

C: I, but, but my point… but I… Jason, I like your point is that he… I didn't think about it. You've brought in so many good ways of looking at these three movies that I have watched a million times that I feel like I've missed so many things, and I can't wait to watch them again based on this conversation. So thank you. I wanna say thank you for that.

A: I’m gonna say check out Jason's TikTok because… check out Jason's TikTok because it's gonna blow your mind.

C: Okay.

A: Because I only recently discovered it.

C: Yeah. I have to put it back in my phone again.

A: The kismet of you being a guest is just craziness. But you wanna talk about, like, I never thought… oh my god, I never, I never knew that. So I feel like that's kinda what you do. That's like…

D: Well, and I like that… I like that you're doing it on TikTok as well, Jason, because I do think… I, I think there is a…. now, just looking at my kids and their peers, I do think there's a hunger for curation. They want to be told what the good shit is. There's so much of it. Film history is fairly daunting now. I, you know, I… when I became a film freak at, you know, when I was a kid, I look at it now, it was the ‘70s. I was dealing with like 40 or 50 years of Hollywood history that I was kind of absorbing. They now have a century of stuff and pop culture has only gotten louder and faster and bigger and meaner and noisier. So really… navigating all that, I think they want to know… like they, they… and they're curious. And media literacy is not impossible for them. I think it's got to be taught, though, and I think one of the things that you do so well is you really provoke people to question the thing they're watching or interrogate it in some way as they watch it, not just passively absorb. And I think that's valuable, man. I think there's real value in teaching younger people how to do that.

A: And, and part of it… younger people…

J: Yeah. Well, part of it is knowing the context of what you're watching. Because I think a lot of these films… and even The Matrix, too, which… that's a film that, again, it's hard to overstate what that film meant in 1999 and the whole metaphor of, if you're used to… and not to start, not to slip in an entirely different film to discuss, but the idea that your previous big pop culture touchstones in terms of, like, fantasy and adventure was about there's an evil empire growing, and we, the down to the earth farmers and the, the brave hearts and the Scottish and the hobbits and the whatever, we've gotta rise up and and take on this evil empire. We've gotta unite. And here, along comes The Matrix that has a completely inverted, like, metaphor where it’s, like, no, you've already lost the war. You're, you're living a life where you're not in touch with anything real. In the metaphor that uses it, you know, you're just in a simulation, but, you know, that meant one thing in 1999. Today, when you see people who believe themselves to be political activists, but all they do is post…

D: Yeah.

J: … like, they're full time Twitter, and they just get into arguments with right wingers on Twitter, and they think that's activism. It’s, like, okay, that's almost too on the nose for a metaphor of The Matrix where you're, you think you're fighting a war, but in reality, you're just in a cocoon. You're just sitting at a desk and typing stuff in front of a glowing screen, and the people in power do not care at all about what you're doing here…

D: Yeah.

J: … that the system has found a way to make you feel like you're doing something meaningful by creating all of these placebos where it’s, like, well, I'll create this meme, then I'll put it on Facebook. And I've, I've, I've struck a a blow in my war against Trump or whatever. And, man, that's the whole thing with the fact that that metaphor of the pod and the simulation and you thinking you're accomplishing, like, everything you're doing is actually just fake and the system has created it for you to make you feel like you're doing something miserable. The fact that that metaphor was early, early days of the Internet. When they wrote this thing, the Internet wasn't yet real. It was, it was all chat rooms and BBS boards and stuff like that… IRC. And the fact that it was before social media, that's why I think it was so difficult for them to try to make that fourth film because all of the, the metaphors are different. It's almost too on the nose now. You, you can’t, you can't make that movie new again because everything that happened, everything that is trying to give you a, a… to symbolize has just… those trends have gone, have exploded exponentially…

D: Yeah. Yeah.

J: … so you can live an entire life staring at a screen, and people do. And you can have no friends in real life, where all your friends are just, whatever… influencers or, or whatever. And then, you know, 20 years from now when everybody has an AI best friend, it's gonna look even more prescient. So I… yeah, I don't know. It’s, it might be one of the best examples that we're talking about here. It just holds up better because of… if you take it out of that, out of that subtext and just watch it as an action movie, you can just do that. And I think that's one where you could show it anywhere in the world, and people would get, oh, yeah, it, it's cool action stunts against the the evil agents. But I, I can’t… I can't make somebody watch that like it's 1999 again. As with all of these, it just doesn't mean the same thing.

D: But when you're talking about context, I think the, the thing about '99 that is so culturally contextually important is we had the luxury of being bored and feeling oppressed at a time when objectively, we should not have been bored or felt remotely oppressed. It was the end of a decade of really forward progress in almost every way. And I think that the end of that decade was pure potential, it kind of felt like, artistically and culturally. And the fact that it all shut down a year later and everything changed was because all of a sudden, there was an actual something worth being upset about or scared of or freaked out about or anxious about. And all of the malaise and all of the freedom to be bored was gone. So these, this whole genre of movie, basically, this is the moment the bubble pops because you really can't ever be these people again. That it’s, it's an expression of something that doesn't exist now. Now is nothing but anxiety. And it's real anxiety. I, you know, you're talking to kids who are watching movies now are coming out of ten years of what I can only imagine must feel like the apocalypse if you are a child right now or a teenager right now. I can't imagine how genuinely anxious everything must be. So movies like this, I, I truly feel like if you can't set up that context, they just won't understand any of it. Like, these movies do completely feel like a different world in time.

When you sent your movies over, I thought about first the 1999 film as the response that I wanted to send you. But instead, I picked a movie that feels like it could be taking place on the same street as Fight Club, like three houses down. Literally. Because the house in Fight Club is so memorable and so iconic, and I feel like the house in 1987’s Orphans, which is based on a play and you can tell, is very much the same thing. It is a dilapidated kind of end of the world by itself house where this entire emotional thing plays out.

[trailer for Orphans plays]

D: Jason, you ever heard of this movie or seen this movie before this?

J: No. Not at all. Even though it's got a lot of famous people attached to it, I get the sense either it was not a huge hit when it came out or else it didn’t, it didn't stick in people's memories.

D: MGM basically… it was like a ten-screen release and then straight to video. They basically didn't know what to do with it. And…

J: Okay.

D: … you would think with Alan J. Pakula as the director…

J: Mhmm.

D: … that would have been something, but he was having a, he had a rough ‘80s. The ‘80s were not great to him and vice versa. Sophie's Choice happened early in the decade, and then he just kinda struggled. He didn't make a film for six years after that. And then when he did, that one wasn't great. And then he made this one and it just barely happened. It's, you know, the proverbial tree falling in the forest thing. Just nobody got a chance to see it. I saw it in '87 and I really fell for it. I was in the middle of… I loved Matthew Modine at the time. I thought this guy is going places. That was the same year as Full Metal Jacket. I thought he was great in that. And I walked out of this movie convinced that Kevin Anderson was going to be a household name. I was, like, I just saw one of those performances where everybody's gonna talk about this dude for the next 25 years. Nope. Crickets. And it blows my mind. I love to show this film to people. I love to tip people to this movie just because I don't think anybody knows it exists.

And it is an inverted way of getting at the idea of masculinity and role models. Like the films that we talked about… Fight Club is, you know, a movie where there are no fathers anymore. It's the Charlie Brown world. All the fathers are gone and there is no fathers. There's no role models. Who do you look up to? Who do you have? And this movie is these two brothers who have basically been on their own for so long and their dynamic is ossified at where they were as children when they were left on their own. And so they've never really changed. The dynamic they have is this dynamic of these two children who now have a house and live by themselves and really have no other world. They are each other's whole world. And then somebody comes walking in and everything goes haywire emotionally. Had you as… and, Aundria, Craig, had you guys heard of this one before this?

A: Not at all.

D: So what was everybody's response? What did you guys think of it, having seen it?

C: I I love… it is very much a play, right? It's almost just a filmed play, really. But, you know, Albert Finney, man. I mean, what the hell? I mean, just chewing it up and just… it's very Brechtian in a weird way. Like, it's just a weird… I loved it. I, I really did. And, and you're right. I, I, I can't even remember the… what's the guy's name? That was supposed to be..?

D: Kevin Anderson.

C: What else was he, has he done?

D: Sleeping with the Enemy with Julia Roberts. He's the nice guy that she ends up with. And that was a few years after this. And he's had several roles like that. He's had TV stuff and things, and he's good. He's just never really popped. And…

C: Okay.

D: … I looked at this, and I thought for sure, man, this was gonna be a dude who everybody was gonna wanna hire immediately for everything. How about you, Jason?

J: Well, this, I didn't know if you're you're even aware of this… the setup of this film, not the specifics of the location or the characters, but the concept is the same as one of my books. There's a… I have a scifi series, and the first book is called Futuristic Violence and Fancy Suits, and the setup is you have this wealthy mobster who basically knows he's going to die. You don't realize it, but he kind of decides to do one last attempt at redemption. And in my book, he finds this, this daughter that he had never had anything to do with. He had knocked up a, like, a, a stripper, an exotic dancer, and he goes and finds her. And spoiler alert for this book, he basically leaves her his whole criminal organization. So the… it takes place in the future. So it's like this futuristic world where you have people with, like, cybernetic implants and and all that stuff, and it's this very dark satire of this young woman who lived in her trailer park who, through a convoluted series of of events, finds out she now runs this organization. But it's the same deal where you have someone from outside her world who has tremendous, like… money is no object.

D: Yeah.

J: Like, swooping in and saying, making a deal that she, not for one second, thinks this is a good thing or this is gonna be fine and and dandy. But it's like, hey, all of your, all of your problems are now nothing. Like, here's $50,000. Do whatever you want with it. And to her, that's like all the money in the world. But to him, it’s, it's nothing. It's his, it's his play money. So it has that feeling of father figure comes in, and it's somebody who not… doesn't just have a lot of money, but they made it in, you know, bad bad ways.

D: Yeah.

J: We've got… and so, and then it does the thing that I like to do where there's a different main story going on. Like, the thing that would normally be the main story, we don't see.

D: I love that.

J: It's happening off to the side. It, it’s… and I know some people have compared this to, like, if you filmed a a play from the other side of the like, from behind the sets. Like, you just get a hint of what's happening. So here, the actual drama is between this, like, some sort of a power struggle among these mobsters, and he has crossed someone. And there's these packages. There's tons of money being thrown around, and that… he is on a collision course with some sort of a doom. But you don't know any of that because you're not, that's not the POV of the story you're watching. You're watching these other people that would, could be kind of like a tangential characters in a different story, and you're only watching them. So this guy is kind of coming in and out of their lives, and you're seeing kind of hints of his life. But you're seeing the cramped and claustrophobic world of these… you know, one guy, like, the, the young, younger brother doesn't go outside. He's got agoraphobia or, or some sort of disorder that… and then the older brother is just permanently stunted at, at age 16 because he never had a role model. So they have this house that they're just slowly trashing. They don’t, you know, they probably… neither of them have, like, driver, driver's licenses. They're totally off the grid and all of that. And so it is, as you said, it's kind of seeing these two people and how they behave, and you slowly learn, oh, it's because they have never had a single role model, and so they're just stuck in this phase of their life. And you kind of assume that when this mobster comes along, it's going to go horribly and that they're all gonna wind up dead, but that's not what the story has, has in store for you. I mean, kind of the way it plays out is almost subversive because it's a very, like, it's tragic, but he… in the end, it's like he kind of… this is the growing up moment for everybody involved.

D: I dearly love the scene where Albert Finney is tied up and gagged and starts to set himself free in stages. And Kevin Anderson's in the house by himself watching this happen. I love that whole sequence. And it's where I think Finney really takes control of the movie. And you realize, oh, Finney is gonna run this show. And so much of this is about him controlling… it’s, it's just dynamics. It's, you know, Anderson versus Modine, and then what happens when Finney comes in and starts to, to get in the middle of that? The encouraging shoulder squeeze versus the, the way he has to handle Matthew Modine, who's an animal, just a cornered animal in this movie, and so angry and so unable to even articulate any of what he's angry at. I think all three of them do really special work, but it's because they all get the tone of this thing. And they're all walking this really… it feels like, it doesn't feel real. It doesn't feel like it's a gritty, realistic movie. It's very heightened. And Anderson's performance, I think, could annoy somebody. But I love it. I love the sort of tone they strike. And I think he plays childlike versus childish. And that's such a hard line to negotiate sometimes. Craig, you said you had not seen this one either?

C: Oh, no. I, had not seen it. But, yeah, I, I just again, I, I liked it. You know, you, you, you mentioned the house, and I think that's probably what sparked it. But I really did love the transformation of it as they, as they, as they got this nurturing character to, like, put it back together. You know? It’s… I just love, you know, it's always nice to see… I don't know. My house when I grew up was so dilapidated that it's always nice to see rejuvenation of, of your, of your space, that I really did enjoy that as, as, you know, parallel to the story. It was really great. I love that.

D: I think there there are several scenes in this movie that I, I think are kinda all-timers. And in, in… I can only imagine how well it works on stage. But I love the scene where he comes home and tells the story about the train and the guy that wouldn't close his legs. And then they play the hypothetical…

A: Yeah.

D: … and I think Anderson's choices during the hypothetical, when he starts singing and when he’s…

C: Yeah.

D: … he's really tough. It is such a great funny transformation for him. I love the scene where Finney convinces him that he can open the window and feel the rain for the first time.

C: Yeah. Yeah.

D: It's just a movie with all these great little human moments, and then it's got a great little sucker punch at the end. It mystifies me that when you get a film like this as a studio, you just abandon it. Like… and I think the late ‘80s were not a great time for small sort of independent minded movies. This one feels like a film that, today, would do the festival circuit first and would be on the festival circuit for a while and it would build some buzz and people would know what it was by the time it finally hit a theater. And I don't think that pipeline existed for little movies like this. I don't think there was the same kind of build up for the same ramp for them to be able to build buzz. I think it had to be much bigger immediately or they went away. So… yeah…

C: I’m just curious as to… I mean, the, the process of looking at this movie and going, yeah, let's make this. Like, it doesn't make any sense this movie would get made at all. Even in 1987.

A: Yeah.

D: I think Pakula… You know, he, he had such a great sense of material that he adapted, whether it was as a producer in his early nomination for To Kill a Mockingbird or the books that he would buy. Right after this is when he did presumed innocent, which I think is his last truly great movie. And he was very much about just finding a piece of material. He didn't write the stuff himself, but he would find a piece of material that he loved and figure out, oh, yeah. I know how that should work on screen. And clearly, he knew what to do. Like, his… the way he stages, this way he builds that world for them is so great. And immediately, just watching when Treat comes home the first time and Philip’s bouncing around the house and stuff, there's such a lived-in quality to it. Like, he clearly rehearsed them. He clearly let them really get comfortable with each other and with the space. It's a movie that has all these little textural things that really mark it as a great filmmaker at work. But yeah, you can tell it's just something that rang some bell in him. And God, the minute he found Finney, I would have like as a director been like, I'm done. I did it. I got it. I got, I got Albert Finney. This is gonna work. It's gonna be great.

C: Yeah.

J: I think if I were to try to recommend this film to somebody, I would warn them that it's very stagey.

D: Yes.

J: And I don't just mean that it all takes place in the same house. It's because… for example, it's not necessarily a criticism. Maybe my most [watched] film of all time is Glengarry Glen Ross, which also feels very stagey. One room, people go on these monologues. Like, you can tell, like, you can just see how that would play on the stage, the way that the characters interact. And they… here, Matthew Modine is giving a theater performance in my…

D: Oh, right to the back wall.

A: Yeah.

J: Very, very broad, very…

C: Yes.

J: Can you all hear me in the back of the room? There's no subtlety in his character. He flings himself onto the sofa and kicks up his leg. It's all very big movements, and I can see people viewing that as, like, being a bad performance or a cheesy performance. But it’s, it's the, it's theatrical. It's very… I don't know if stagey is a word that people use, but it feels like they're acting for the stage. There's this, this method of the… if they wanted to be more naturalistic, they could have done that, and they preserve… because I, I think the screenplay was written by the playwright who did, did the play. So I think it very much was just, you know, all of these speeches and all that stuff… that it feels like they're doing a performance. I don’t… I, I don't think that's an accident. I don't think they were trying to do something else and it failed. I think they wanted to capture the play. If people didn't connect with it in 1987, I could see maybe that being a reason…

D: Sure.