Podcasts are funny things. They are, ultimately, driven by personality.

The podcasts I love the most are the ones that feature people who have some genuine relationship, and what I respond to the most is when it stops feeling like a show and starts feeling more like you’re just hanging out with these people, having conversations. When ‘80s All Over was cooking with gas, it was just Scott and Bobby and me having a real discussion about those movies and inviting you guys in.

I wanted to do a run of warm-up episodes with Aundria Parker and Craig Ceravolo so we could get comfortable with each other. The thing that’s been so gratifying as we’ve been doing this is that we are naturally starting to fall into a certain rhythm. I look forward to these recordings, and that’s a very good sign. If I feel that way, then hopefully you guys will, too.

I know that these early episodes are technically rough, but by season two, we’ve got it all worked out. The challenge of this show is that the three of us are in very different parts of the country, and we’re doing this entire show juggling remote elements. It’s the same challenge we faced on ‘80s All Over, and without Bobby Roberts at the production board, we’re learning all of this all over again.

For this episode, we each picked a film from the 1950s, and it seems clear that the three of us are always going to come at these assignments from radically different perspectives. That means the show is working. That’s exactly what I was hoping for. It guarantees that we aren’t just picking the same types of things every time out.

I’m going to be publishing one of these warm-ups every week until we launch the second season, where we begin to welcome guests to the show, in January of 2025.

Anyway, let’s jump right in, and please enjoy the transcript posted below as well as the audio, which you can download from this page. You can also find this show on Spotify and Apple Podcasts now, so feel free to rate and review us there if you like what we’re doing!

DREW: Hi everyone. My name is Drew McWeeny and welcome back to The Hip Pocket.

Everyone's got movies they love. Good movies, bad movies, movies they love for all sorts of reasons, and we carry them around in our hip pockets waiting to share them with other people. That's what I've been doing in print for 25 years now.

I've invited some friends to talk about those films with me as well as the films that are important to them, and you're invited to join that party every week. This is our third episode. I am definitely getting more and more excited about checking in each week with the people that I'm having this conversation with.

First, I'm joined by my band leader and my good friend, Craig Ceravolo. How are you doing, Craig?

CRAIG: Hey, Drew. How are you?

D: I'm good. How are things going with you this past week?

C: Let's see. I don't even know where to start. (laughs) Everything is great. Let's just put it that way. All is well.

D: I am, I'm happy to hear it. It's, we're deep in the dog days of the strike. I'm feeling it. My girlfriend's feeling it. Like, it's been a been a wild week, man. I just, you know, I'm ready for this whole thing to be over, but it's nice to have this as a thing to check in on and look forward to right now, especially because you and I get to talk to my big-brained co-host, Aundria Parker. What's up, Aundria?

AUNDRIA: Hi, guys. You're too kind. You're too kind.

D: How, how've you been?

A: I've been, you know, alright. I'm ready for fall. I think we're all just kind of alright. We're getting through. We're doing what needs to get done to get to the next day.

D: I think that is, that is pretty much 2023. With that in mind, let's take a look back this week at the 1950s.

It was good. America got fat. Everybody got, everything was fixed. Everybody's happy. Yeah, Joseph McCarthy dicked things up and the Rosenbergs were executed, but we got the polio vaccine. We got the Mercury projects. The civil rights movement started to ramp up in the ‘50s, and we added two new states just in time to kick off a cold war.

You know, I think we look back on the ‘50s, and I know that I personally have this very rose-colored picture of it in my head, but the reality is way more complicated and tumultuous. I think that the films that we're gonna talk about this week kind of reflect a different version of the ‘50s.

So when you first hear that phrase, the 1950s, what do you think of, Aundria? What's the first thing that, like, pops into your mind?

A: I mean, I definitely see, I see black and white. I see housewife. I see dad coming home to two well-groomed children. Kind of that.

D: Mmhmm.

A: Very innocent, a veneer on something that is not necessarily the truth of what's going on.

D: I think that is very much like the version of the ‘50s I have in my head, too. And Craig, you're about the same age I am. Did you grow up on, like, Happy Days and that first wave of ‘50s nostalgia when it hit in the ‘70s?

C: Oh, yeah. You know, it's, it's Potsie. It's Fonzie. It's all of that. You know, we had Grease. You know, the boomers had this nostalgia for their youth, and we had to live through it.

D: And it's weird because we got to live through two different moments as they digested their past. First, they had to digest the ‘50s for about fifteen years, and then they get to the ‘60s for about fifteen years. So I lived through those two decades for the first thirty years of my life, which is fucking weird, but that is the way pop culture works. I know when I, look, when I think about the ‘50s now, I think that it is an era that was marked by a… I think what you said, Aundria, is very true, a veneer, a false top, and that it is a much weirder and more complicated decade underneath. So the film that I picked for my first movie is one that I think is a seedy version of the 1950s, and I kinda love it. It is a film that is as much of a direct influence on Tarantino's debut film Reservoir Dogs as Ringo Lam's City on Fire was. This is a really solid meat-and-potatoes crime movie from a director named Phil Karlson and I wanna know what both of you thought about Kansas City Confidential.

[clip from Kansas City Confidential plays]

D: This guy, before I throw it to you guys, I just wanna say this guy, Phil Karlson, who directed this, was better known for movies he made later. Ben? The, the rat movie from the ‘70s? And Walking Tall. And Walking Tall was an indie film. He had a lot of his money in it. Phil Karlson died riiiiiiiich because of Walking Tall, but he struggled. Like, there were a lot of years where Phil Karlson was directing Z movies, not even B movies. He couldn't get the meetings for the B movies. And I think this one was supposed to kick off a new company that was gonna have a distribution deal with Columbia. This was their only film. They made this thing and then got out.

And I don't get it because I love this movie, man. It is so stripped down. It is a crime film about a guy, Mister Big, who plots this crime, and the whole thing hinges on the fact that all of the criminals he picks, they're all gonna wear masks every time they meet. They're all gonna use code names. Nobody will know anybody. Nobody can finger anybody. They'll all get away scot-free. But of course, it can't go that way. Mister Big has his plan that is much more complicated than that, and they pin the whole thing on this poor, innocent delivery truck driver who they send to jail. And when he gets out, he wants his.

[clip from Kansas City Confidential plays]

D: That is what the movie is. It is, he is going to figure out who did this to him, why they landed on him, and get something for it. And I love it, man. I think it is such a good little movie. What'd you guys think?

C: Aundria, would you like to go first?

A: I would love to go first. I think the refrain I kept saying was, why don't they make movies like this anymore? Okay? So like you said, 1950. I think it was 1951 when it came out. How timeless did everything in this movie feel? Every, the dialogue, every exchange, every double cross, every triple cross, everything felt… I mean, if if it wasn't made then, it could have been made now. I know that sounds silly, but, man, it was so good, and it just kept moving. And no idea where it was gonna go at any turn. Yeah. I just kept saying, man, I would love for them… I don't want them to remake it, but I would love to see more movies that are just, you know, smart people being mean to each other. Trying to pull a fast one.

D: I love the use of… during that whole sequence where they go to Mexico, I love the fact that that's Catalina Island here in Los Angeles, which if you if you've ever been to Catalina as a tourist, you take a ferry out to it. It's like an hour from the mainland, and it is this weird little touristy spot that has developed over the years that you go, you spend way too much money, you stay in a crappy little hotel, and it's fun.

C: (laughing) I guess?

D: But they use it as this Mexican village that they're in, and every time they cut to it, it makes me belly laugh. I cannot get over the location. It's so great. I love the supporting cast in this thing. The three guys who, the three criminals that are brought into this plan by Mister Big are played by Neville Brand… he's the cop killer. You've got Lee Van Cleef, who is the womanizer, and that's a wild casting choice for Lee Van Cleef. And then Jack Elam, who's like the degenerate scumbag gambler. And all three of those guys go on to these huge careers as character actors, and they're all terrific. And then you've got the main dude, who is played by John Payne. Did you guys recognize him from anything?

C: Of course.

D: Okay. Good. Because I grew up with this dude every year watching Miracle on 34th Street when he defends Santa Claus.

C: He made me believe!

D: He's the lawyer who gets Santa off the hook, and then you see him in this, and it's like, oh my god. It's like if Fred Rogers had made this movie where he was this ice-cold murderer that he made 5 years before Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. You're like, what the fuck is this? Like, it's great. I love this dude in this movie.

Craig, what did you… what was your take on that?

C: That was my favorite bit of casting. Like, you know what I mean? Like, I love Miracle on 34th Street so much. All I could see is him going to sleep with Santa Claus and asking about the whiskers inside or outside...

[clip from Miracle on 34th Street plays]

C: That's all I could think about when I was watching this movie. This is John Payne.

D: So good.

C: So good. But he's so charismatic in this. Like, he is… you know, that's why Jon Hamm is who he is. Jon Hamm has this old Hollywood quality, and I think that it's a direct line from Jon Payne to Jon Hamm. Jon Payne? Yeah. Yeah. To Jon Payne. To Jon Hamm. I mean, just that chiseled rugged dude…

A: Yep.

C: … that gets himself in this situation and is just so relatable. I mean, you know what I mean? But I loved it. And I… here's the thing about this movie. My attention span has gotten worse as I have gotten older. And you cannot sit and scroll on your phone. You have got to pay attention to this movie. That is intricate. It is complicated. And if you do not catch everything that's going on, how this thing unfolds, you will be lost. And the payoff is brilliant. It is fantastic. I loved it.

D: Awesome. I'm so happy, man. This is… and this movie has been treated so badly over time.

C: Really?

D: Because it was… yeah, it was, it was one of those movies that, because it was kind of, very, very low budget when it came out and it wasn't a big hit, it just bounced around from distributor to distributor. And, eventually, everybody kinda thought it was public domain. So there's a lot of really shitty versions of this out there.

C: Okay.

D: The only one that exists that is any good to look at is the MGM print that they put out because they actually own the negative. They had it to do a better version of it. So I think the one you guys saw was the decent one.

A: Yeah. It was.

D: But it I mean, it has been kicked around and was and, obviously, that title, Kansas City Confidential, that was the first, like, “Blank Blank Confidential.” Yeah. And everybody borrowed from that. Everybody used that title style. I do feel like this movie became influential even though it's kinda like The Velvet Underground. It's, like, never a mainstream hit, but everybody who saw it made a crime movie. Right?

C: And Dragnet. Right?

D: Oh, yeah.

C: I mean, it feels like Dragnet pulled all of it from this. You know, the matter-of-fact introduction, like, “This is from the confidential files of the Kansas City Police Department.” Like…

D: Yep.

C: … it, it's so influential. It's so much so that it seems cliched. Right?

D: A little, yeah. But it's… it's funny. You can see where… you can see the trickle-down from this thing. Like, the people who borrowed from it, and then the people who borrowed from the things that borrowed from it. And it's one of those movies where when you finally see it and you look at when it was made, you're like, “Oh, this had to be the start for a lot of things.” Like, this had to be the moment where a lot of people got these ideas. Right.

A: You have to remember it was the… it was the die that was cast… you know what I mean? Or whatever that metaphor is. It was… it was the one that started it as opposed to watching it and we're like, “Oh, that's from, you know, this, that.” No. That was it. That was the first one or you know, or one of the first and… yeah. Man.

C: Yeah. And Tarantino lifts that Mister Big, like, nobody knows who anybody is. So brilliant. And I don't even… I'm not even saying that to… I mean, it's, it's beautiful. They're all mad.

D: I think that's fantastic. Yeah. Exactly. It's, it's the exact thing I like about him because he is, you know, he even calls himself out at the end of Kill Bill when they're watching Heckel and Jekel, the magpies. He's a magpie. He steals constantly, but he steals brilliantly. And he steals the way you're supposed to, which is, he's seen so many things that he is a blender. It goes in, and then it all gets blended up into something different and comes out. And, yeah, you might be able to say, “I think this might have started here,” but it's never the same the way he does it. So Reservoir Dogs is not this, but you feel this in Reservoir Dogs, absolutely.

[clip from Reservoir Dogs plays]

A: I was just listening to the Smartless podcast, and they were interviewing Steven Soderbergh. And he was being so humble, in that he's like, “I'm just a synergist. I just take things that I like from other movies and put them together in my own view.” And he kept, you know… almost as if there was no creativity on his end. He was just stealing, stealing, stealing. And, you know, there's a whole book series and art series called Steal Like An Artist. You have to be an artist to know how to steal properly, to know how to give homage properly. And, you know, certainly Tarantino is one of the guys…

D: I think Soderbergh is a perfect, second example of that and you're… you're right. That's very humble of him because he is a terrific stylist. And, you know, there is so much Richard Lester in what he does. And it's nakedly Richard Lester, like freeze-frames and the way he holds split-screens and things. He absolutely is in love with that man and loves his filming, but when he does it, it feels like it's his. Like, the Out of Sight moment where George Clooney throws his tie and it freeze-frames, that's a Richard Lester moment, but it's also awesome. And it's so perfect for that moment, and it sells it tells you everything about Clooney immediately. So, yeah, it's… you're right. It's how to steal, how to use the things that you've seen, how to pull those references, and then use them in a way that is just vocabulary.

[clip from Kansas City Confidential plays]

D: Craig?

C: Yeah.

D: I’ve got some big feelings about your pick today.

C: Yeah.

D: When you talk about the when you talk about the fifties as a decade that presents one way on the surface, but which is grappling with all kinds of things underneath, that might be the plot synopsis for Douglas Sirk's Imitation of Life.

[clip from Imitation of Life plays]

C: I love this movie so much. I don't know where I saw it, but it really hit me when I saw it. And it, it… you know what it is? Here's what it was. I've said this before, like, I filter so much stuff through music and there's an REM song called “Imitation of Life.” You know this song?

D: Mhmm.

C: Okay. So, obviously, they lifted the title from this film. So I had to go back and find out what the film was, and it has nothing to do with the movie, of course. But, it's a beautiful… it's just beautiful. The color is beautiful. The story is beautiful. It's heartbreaking. And, you know, the gospel at the end, like, the tragedy… I'm not gonna, you know, I want people to see it. But it is an amazingly beautiful film to watch just as an, as eye candy for one, just the luscious colors of it.

But, obviously, the story is important, especially set in the ‘50s, as you said, Drew. You know, civil rights, you said that. That was the beginning of the civil rights movement, especially down here in the South. You know, that's, it's really something that we really are sensitive to. And to see this, you know, it's got a direct line to Oscar Micheaux's silent films about passing. Right? About, you know, African Americans passing as white folks. It goes right to the movie Passing, which is an amazing film from a couple years ago. But I love the subject. It's really, I think it really tackles it in the best way possible.

D: Well, I think Sirk is, he's a smuggler. He's one of those guys who, every film he made… they're so glossy. They're so beautiful. And they're just, as a, a thing to look at, he makes these very lovely objects that I think studios loved, and they saw them as women's pictures, and they were seen as softer. But Sirk is a social commentator and a realist, and there is an undercurrent in his movies where he is constantly pushing against that pretty surface. And I think he never did it better than this. This is his last big Hollywood movie, and, I think the Lana Turner performance is terrific.

C: Yeah.

D: But I think the the way the film tackles this, really head-on, and the, the younger, the girl growing up, Sarah Jane growing up… you feel for her. As awful as she is at times to her mother and as, as horrified as she is by her own identity, man, you feel for her because you know when this was made, you know what the pressures were like, and the film does a great job of not soft-pedaling that. So it's…

C: Right.

D: … you understand her all the way through, even when she's breaking her mom's heart, even when she is doing things that feel brutal. And, man, that's the hardest kind of thing to watch because you… it's easy when it's a villain. It's very, very hard when you totally empathize with what's going on.

[clip from Imitation of Life plays]

C: Right. I agree. Aundria, what did you think?

A: I'm gonna be honest with you. It took me a little while to get into the groove of the movie. I watched maybe, like, a half-hour, forty-five minutes? Stopped. I was like, “Okay, I don't think I'm receiving this movie right.” But then I gave it another go, and I was like, “Oh, I get it.” It, it just took me, like, a different mindset. Right? Once I kind of knew the rhythm of the language and what I was looking at and the high melodrama, with these, you know, the thing is, it is high melodrama, but it has these incredibly serious…

D: Yeah.

A: … realistic social issues so woven into it. So once I kind of got on that level and just gave myself over to it, I really enjoyed it. I was kind of shocked and devastated when it was over because I wasn't, I was very specifically not looking at what the time counter was because I didn't wanna know where things were gonna go or where they were gonna end. So when it did finally end, I was just like, “Ohhhhh,” you know? Just heartbreaking stuff. And Sandra Dee was great. I, I, this might be my first Sandra Dee movie. You know? I, I really enjoyed it. Like I said, though, I, I will be honest. It did take me…

D: Yeah.

A: … a minute to adjust to that world, right? To get into that world and then be like, “Alright. This is what it is. This is what we're doing.”

D: Well, I, I don't think you're… I think the use of melodrama, that's, that is probably an important thing to set for people in terms of expectation because it is. It's, it's absolutely sort of overheated in the the way it speaks to you. And so there's, there is that soap opera-y sort of side to it.

C: And you gotta like, and like you, that's interesting that you said that. Because you really do. If you don't know what you're walking into, you're like, this is the worst movie ever.

A: I didn't think it was the worst. Right? Because it is over the top.

C: Yeah. Yeah. No. No. No. I'm not saying you. I'm just saying prepare yourself for it.

D: And it's really interesting because we're gonna… the movie we're about to talk about after this exists in such a different world in terms, in terms of tone and acting style. This is what Hollywood movies were by and large until this point in time. So there's an artificiality there, and everybody's acting.

Lana Turner in this gives an old-school, no-shit, movie star performance where you know her assistants are 4 feet away at all times and it's perfect for this. Like, you want that at the center of this. You want that to be the thing that poor Sarah Jane is looking at her whole life as this world that she can't have or be part of. Lana Turner embodies that. Like, it's a really smart casting choice. But this is definitely not played as realism even though the things they're talking about are so grounded in that moment. So that is, I think, a, a… something we don't do anymore in film. We really don't make these now. I think that tone is gone, and I think it's a really, really hard thing if people try to do a throwback to it. I know Todd Haynes with Far From Heaven was absolutely doing this.

C: Yes! I’m so glad you said that.

D: I mean, that… that's what he's doing in that way. He is absolutely making this kind of film and I think [doing] Sirk in particular, but you watch Julianne Moore's performance in that movie, and Julianne Moore is an actress who understands the artificial or the real and what a director's asking of her, and she'll give you either. But she will make a choice, and then you are gonna have to live with it because it's, it's, she doesn't, she doesn't walk the middle line. She goes one way or another.

C: Yeah. That's a great touchstone. Like, I love Far From Heaven so much, and it's a, it is beautiful to look at, too, but I think he's pulling… that's a direct line again from this movie. And I think maybe Revolutionary Road was a little over-the-top, melodramatic…the Sam Mendes movie. You know, it's like, I think that he was trying to lean into that, and it didn't work. And I don't think that people, that tone really works anymore.

A: I think people are too cynical for it.

D: I think both too cynical for it, and I think… like I said, I think Sirk was using this form as a way of sneaking things through. Like, if it's this heightened and melodramatic, you're not gonna realize that I'm telling the truth in the middle of this thing. I'm gonna put this. So I think that he liked that artificial style.

I do think there's filmmakers now who, although they aren't the same kind of filmmakers as Sirk, they use artificiality the same way. I think my closest example to him today would be Spike Lee because I don't think Spike Lee's films take place in the real world at all. I, I think Do The Right Thing is not the real Brooklyn. It is the emotional Brooklyn. It is the way it feels in those landscapes. And I think Spike is so good at heightened reality and a sort of Spike Lee world that he has created, which allows him to, in his overheated larger-than-life way, tell the truth. And I, I do. I think it's a really hard thing to pull off. And I, I think you've got to… as a filmmaker, Jordan Peele is trying to to find this way to be very heightened, but also very honest. And I, I admire that in a filmmaker. I think it's a tricky, tricky thing.

C: I think Wes Anderson has just gone off completely and doesn't know what he wants to do. But, you know, I say that because his is this hyperreal, like, fantasy, but I don't know what he's trying to connect it to, but maybe I don't resonate with it. I love Wes Anderson, but it's… it just made me think of this, compared to what you're talking about with… because I love Do the Right Thing. It's one of my favorite movies of all time. But it is like this surreal, like, almost, stage play event or, or film. And you know, and I think that, again, imitational life is very much that way. And I only brought up Wes Anderson because it's so artificial that, you know, it is almost… there's, there's all… and I hate to say this. There's almost no substance to it with the artificiality. The artificiality is it's… it's, it's the thing. Right? But I could be wrong. I'm not really, that's not really fair for me to say. But I'm just saying there's, there is some sort of depth to the artificialness of this movie, of Imitation.

D: I think, I think his last film is all about that. I think Asteroid City is the first time he's ever specifically head-on texturally dealt with the idea that the artifice is part of his process, and he needs that. He needs that remove in order to dig into, like… I think Asteroid City is him directly commenting on what you're saying. “Have I gone too far into my style or is my style the thing that I use to get to what I'm trying to say?” And I, I don't think he answers the question for himself. I think he had to make that whole movie to wrestle with it.

C: Drew, I'm so glad that you're here to articulate what can't come out of my brain.

A: I feel like Drew synthesizes you and I, Craig. Like, we say things, and then Drew kind of puts them out in a way that's more, you know, eloquent and you're… you know? Yeah.

C: It's, yeah. It's like we… I don't wanna speak for you, but it's like me, I just, like, spit out these, like, jumbled up wires, and Drew will take them and unravel them and make them into something.

A: He's our bomb squad.

[clip from Imitation of Life plays]

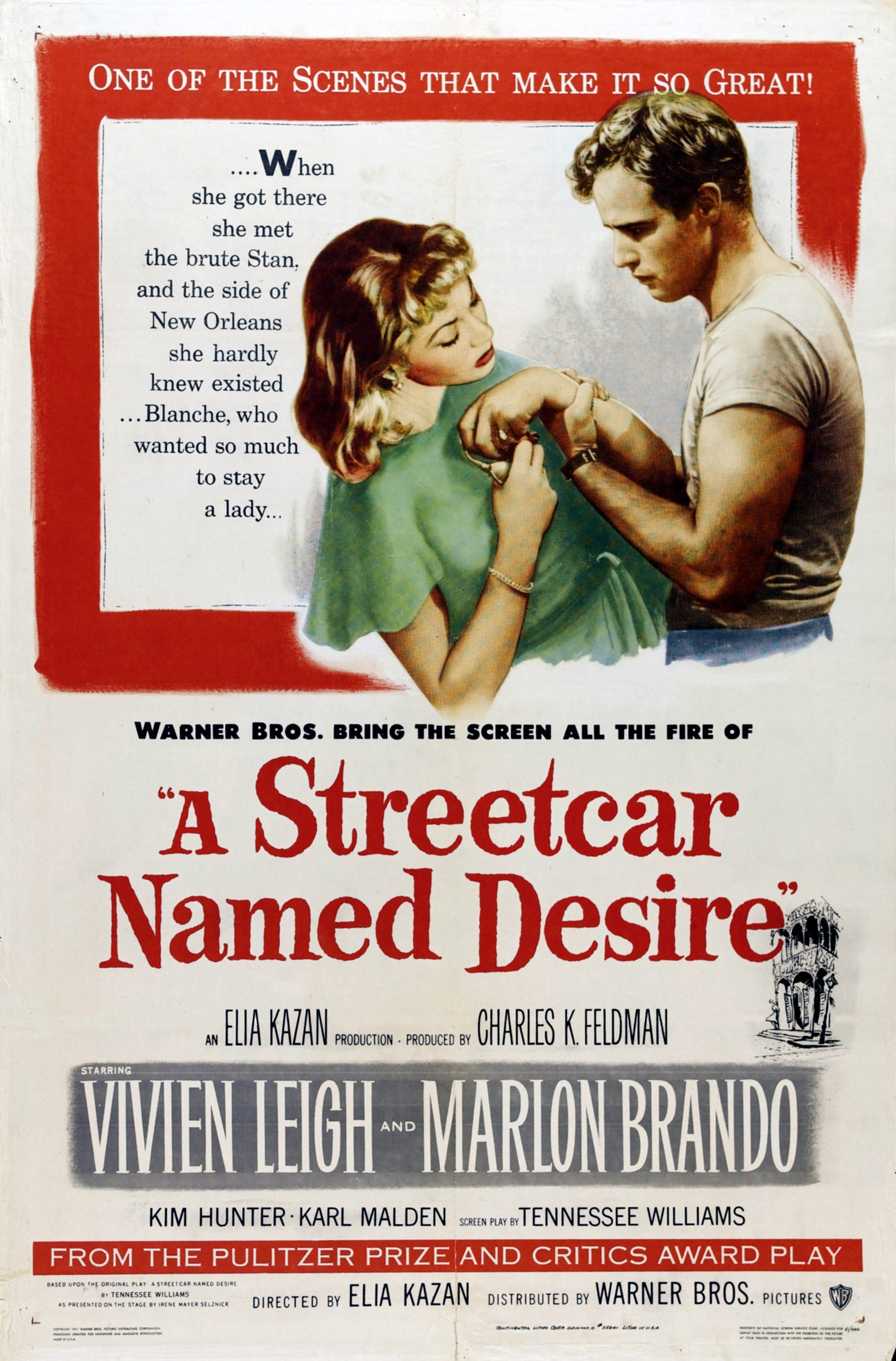

D: When we are talking about, that kind of artifice though, the ‘50s was the moment where film kind of took this left turn towards method acting. And “method acting” really only started in the late ‘40s. So it makes sense that it took a little while on-stage before people went, “Oh my god, there is something really interesting happening here,” and then Hollywood had to make room for it. So the ‘50s was when they kind of embraced guys like James Dean and Montgomery Clift and, of course, the king gorilla of all of them, the late great Marlon Brando, which brings us to your choice today, Aundria. Tell us about the first time you saw A Streetcar Named Desire.

[trailer for A Streetcar Named Desire plays]

A: I saw Streetcar for the first time in high school because we had read the play. And I think we watched it in class, but I was… or, or maybe we watched selected scenes of it, and then after, I went back and watched the whole thing. But I was just absolutely mesmerized by it. Even as a teenager, I had never seen, I probably had never seen a Marlon Brando movie, and I had definitely never seen something that was… I, I don't even know how to describe it. It just hit me in such a way. And I've seen it numerous times through the years since then, obviously, but there is never a lack of amazement at that, like, 12-minute mark when Stanley Kowalski walks into the apartment, and all of a sudden, the rest of the film blurs away because of Marlon Brando, who is, yes, absolutely gorgeous as a young man. But the chemistry that he has with everybody, the…

D: Brick shithouse.

A: … the magnetism of him is, it can't be overstated. It's, it just can't be overstated. It's unbelievable. And he carries this performance of this terrible person through this entire movie who you're still feeling for, and, and he's not even the lead, really. Right? It's, it's Janet Leigh's movie. But.. Janet Leigh? No. Not Janet Leigh. Vivien Leigh. I'm like, she was not in Psycho. Yeah. Vivien Leigh.

C: Vivien.

A: It's just, it's so… it's so much. It's very it's very melodramatic, just like imitation of life, but in in a completely brittier, bleaker, not fun and shiny way.

D: This is what I find interesting about Tennessee Williams, is he writes about fragility. And I think all… in every one of his pieces, there's some character who is so fragile that the world will break them. Glass Menagerie has you know, that's built around that, that poor girl who is that glass character. In this, you've got her unbelievable work as Blanche DuBois, which… she is one of the great characters he ever imagined. And the piece is all about illusion and kinda how carefully constructed people's lives are and how a lot of people depend on lies that they tell themselves and tell other people as the way you get through things. And all Stanley wants to do is strip everybody else's illusions away because he's fucking miserable and you will be too. And it is… man, in 2023, that character is everywhere. The idea that “I'm going to… if I hurt and I am miserable, then everybody else has to live in the same shit I do” is like our driving ethos now, and it is a crazy thing to witness. Stanley is an unbelievably well-written character, but I've seen productions of this where you do not get what Brando brings to it, which is the magnetism that allows him to live like this. Like, I've seen a lot of people play the animal version of Stanley Kowalski, and that's fine. But Brando is, like you said, fucking beautiful when he walks into that room. Like, holy crap.

A: There's no other words for it.

D: Yeah.

A: Yeah.

D: And as a result, Stanley has sort of been allowed to be this thing and has been allowed to become this thing, and I think that's also a very American thing to write about. I think it's weird how many of this… specifically the movie version…. how many of the moments have been taken out of context culturally and now have their own lives?

A: Absolutely.

D: How many times have you seen somebody use “Stella!”, and they use it like it's a romantic moment? Like, it's John Cusack with a fucking boom box outside the window? What the hell is wrong with you? That is the least romantic… like, that is crazy. That is absolutely an insane way of trying to recontextualize that. I've also heard Blanche's line from the end of the… “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers”… I've heard that used in so many different contexts. It's shattering the way it's used in this play. Like, it is not… it is a haunting line. It is truly the end of her sanity that she is, like… so, yeah, I find this whole thing fascinating, and it's perfectly appropriate to the shirt that you're wearing today, Craig.

There are two types of people in this world. There are people who near hear the name Kim Hunter and go, “Oh, the Academy Award-winner from Streetcar Named Desire.” And then there's people who hear the name Kim Hunter and go, “Zira from Planet of the Apes?!” And I have been both of those people at different points in my life. So I think if you live long enough, you are eventually both of them. She's great in this, too. I think, I think so frequently the conversation is about Vivian Leigh and her work and Stanley and his or, Marlon Brando and his work. But Kim Hunter, there's a reason she won the Oscar. She is amazing in this and has to be this, has to navigate the thread between these two giant magnetic forces. And I think that is truly one of the more difficult things to play, is somebody who is in constant danger of being overshadowed or blown off the screen.

[clip from A Streetcar Named Desire plays]

A: Karl Malden as well. Like, there's really only the four of them in this movie, and Karl Malden is doing stuff that is devastating and heartbreaking. And he is playing this person who is a friend of Stanley, but at the same time, they're so different until they're not. Right? And, and he's just a guy. He's just, you know, kind of a shlub who's fallen for this very mentally ill woman, this beautiful, um… he sees her as almost maybe, like, ethereal and fancy and all these things. And, god, he's so good. He's that… she's projecting. He sees that thing that she's…

D: Yeah. Described that she wishes she was. Yeah. And I do think that's… and that's part of what Stella and Stanley have. That's part of what Blanche and, and, I forget his name, but they almost have is the person who's willing to let your fantasy go. The person who's willing to let you live in that is the person that's probably right for you. And I, the end, the ending of the film is slightly altered from the ending of the play. The ending of the play is truly bleak, where she does not leave him. She simply accepts that this is the way life is, and Stanley is what he is. And she does not get morally indignant about the rape and leave. I also think it's amazing that this film navigates that rape the way it does and never says the word.

A: It doesn't explicitly.

D: It totally commits to it, but it it's it is absolutely larger than life in that second break, in that last act of the film. Yeah. So it's… I… that's a magic trick. Yeah. That's a magic trick to pull that off. It is interesting that this is a film built around something that you could not talk about. I think the ‘50s is a decade where there's a lot of that. You're, you're watching dramatists butt up against the edges of what you can or can't say, and they're really looking for the cracks in the Hays Code. So this feels like the last era where they have to dance this dance where you can't say the words.

A: Yes. Yeah. It just… I was…

D: You can kind of do it.

A: Yeah. You can kinda show it even if you can't say it. It just, it's really, I mean, it's so powerful. And I feel like, for it to get through to me at that age and still so many decades later still have that effect on me, it shows how special it is, how powerful it is.

D: It's, it reminds me a lot, film-wise, of the Mike Nichols adaptation of Virginia Woolf, because it's the same thing. It's the four characters, really. And although it feels stagey and although you are still very much in one space, I love how this apartment gets smaller over the course of the film.

A: It does.

D: How it's literal. Like, the sets get smaller over the course of the film so that you eventually feel absolutely trapped in that place. But that's a film thing. Like, that's not a stage thing. You wouldn't do that on stage. It's a gradual effect that, in film, you can pull off. And so I do think it's very cinematic, but it's at that moment where we're making the jump and we're seeing a lot of stage work that they're, they're really trying to find a film language to augment to, like, to to take it to another level. They aren't just straight adaptations. I do think that's important.

[clip from A Streetcar Named Desire plays]

D: Listen. I love this. I… thank you so much, guys. These were, I think, very different movies, and I really enjoyed watching all of them back-to-back as a, it… it is a reminder of what I hope this podcast is gonna do, is you can take one subject, look at it through three different prisms, and get three radically different views on the thing.

I look forward to this. I look forward to talking to the two of you next time about the ‘60s, which is such a different decade. And I think, I think the three picks we made may be the strangest way to look at the ‘60s I've ever seen. So I… yeah, I can't wait.

Keep it in your hip pockets until then and we will see you guys next time.

Share this post